The genealogies of Jesus in Matthew and Luke have long drawn attention because Matthew includes Jeconiah in Jesus’ legal line, while Jeremiah 22 contains a judgment stating that Jeconiah’s descendants would not prosper on the throne of David. Luke, however, declares that Jesus will inherit that very throne. Some interpret this as a contradiction or a theological problem, but the entire issue dissolves once the passages are read in their historical context. The so-called Jeconiah curse is often misunderstood, and modern claims about a permanent disqualification of Jeconiah’s line simply do not align with the biblical text or Jewish interpretation.

The Nature and Scope of the Jeconiah Curse

Jeremiah delivers one of the sharpest judgments in the book when he speaks of Jeconiah, also known as Coniah or Jehoiachin. The prophet declares that Jeconiah’s reign will end in disgrace and that his immediate household will not remain on the throne during the final days of Judah’s collapse. Jeremiah 22:28–30 records the judgment in full:

“Is this man Coniah a despised broken idol, a vessel in which is no pleasure? Why are he and his descendants cast out and sent to a land which they do not know? O earth, earth, earth, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord: ‘Write this man down as childless, a man who shall not prosper in his days; for none of his descendants shall prosper, sitting on the throne of David and ruling anymore in Judah.’”

The meaning within the passage is straightforward. Jeconiah would not prosper, and his sons would not sit on the throne during the final generation before the exile. The monarchy was about to be terminated by Babylon, and Jeremiah’s oracle describes that imminent collapse. The text does not declare a permanent, all-generations curse against every future descendant. It announces the end of Jeconiah’s royal line in his own days as the kingdom fell.

Why Jeconiah Was Judged by God

The biblical explanation for Jeconiah’s judgment is direct and uncomplicated. Second Kings 24:9 states that Jeconiah “did evil in the sight of the Lord, according to all that his father had done.” His father, Jehoiakim, had already been condemned by Jeremiah for oppression, idolatry, injustice, and rejecting prophetic warnings. Jeconiah continued the same rebellion during the final months before the Babylonians seized Jerusalem. His reign was not uniquely wicked in itself, but it represented the culmination of a dynasty that had exhausted God’s patience. The judgment upon him was the natural result of generations of covenant-breaking.

The Danger of Removing Jeremiah 22 from Its Context

Jeremiah 22 belongs to a series of judgment speeches targeting Judah’s kings in the years leading up to the exile. Each oracle addresses a specific ruler’s actions and the consequences for that particular generation. Modern readers often make the mistake of lifting the Jeconiah prophecy out of this context and treating it as a sweeping, eternal curse on the entire Davidic line, something Jeremiah never says. When understood in context, the oracle concerns Jeconiah’s immediate situation and the political end of his line in that generation, not a permanent theological barrier to future messianic hope.

How We Know the Curse Does Not Apply to All Future Descendants

Several factors demonstrate that Jeremiah 22 does not pronounce a perpetual curse on Jeconiah’s entire bloodline. First, the Hebrew word for “descendants,” zera, is flexible and frequently refers to immediate children in prophetic judgment passages rather than all future generations. Second, Jeremiah limits the oracle by saying Jeconiah would not prosper “in his days,” which frames the time period explicitly. Third, the monarchy ended for all descendants of David when Babylon destroyed Jerusalem, meaning no one from any branch of the royal family sat on the throne afterward.

Fourth, Jewish tradition never saw Jeconiah’s line as disqualified. On the contrary, Shealtiel and Zerubbabel were honored leaders of the return from exile. Finally, the Davidic covenant by its very nature cannot be broken by a localized judgment oracle. If God had revoked His promise to David, the prophet would have stated it clearly, and no such revocation exists.

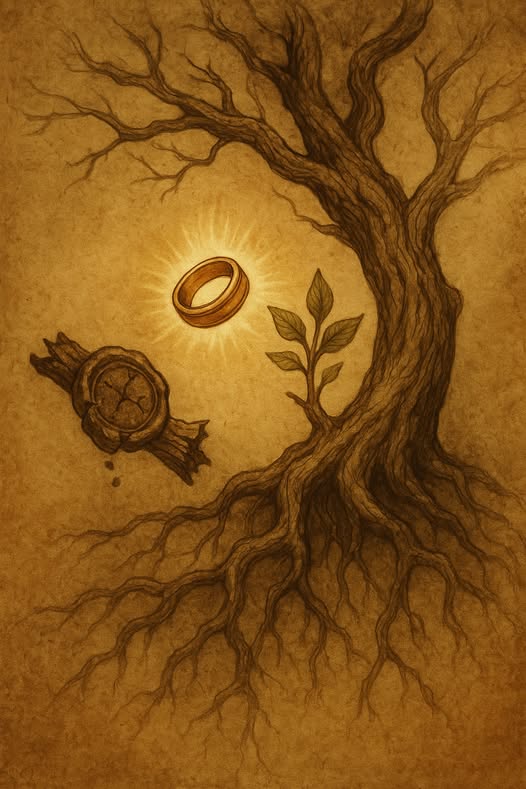

The Role of Zerubbabel and the Haggai Reversal

Haggai describes God making Zerubbabel, Jeconiah’s grandson, like a restored signet ring. This imagery intentionally reverses the earlier language of rejection in Jeremiah. Far from signaling a resurrection of Zerubbabel or a reversal of a still-active eternal curse, Haggai affirms that God’s favor remained on the Davidic line. No ancient Jewish or Christian interpreter imagined that the Jeconiah judgment extended indefinitely into the future. They saw Haggai as a symbolic reaffirmation of the Davidic promise.

The Genealogies and the Virgin Birth

Matthew provides Jesus’ legal genealogy through Joseph in order to establish His official right to the throne of David. Ancient genealogies focused on legal inheritance and covenantal legitimacy, not modern biological mapping. Luke presents Jesus’ biological descent through Mary, expressed in standard genealogical form, while noting that Joseph was only considered His father “as was supposed” because of the virgin birth.

Through Joseph, Jesus receives the legal Davidic claim. Through Mary, He is physically descended from David. Through the virgin birth, He avoids any connection to Jeconiah’s biological line even if someone wrongly interpreted Jeremiah 22 as a permanent generational curse.

Why the Curse Does Not Touch Jesus

Because Jesus is not biologically descended from Joseph, He does not inherit Joseph’s bloodline, whether blessed or cursed. At the same time, Joseph’s legal fatherhood confers the Davidic royal line upon Him. Luke ensures that Jesus is genuinely descended from David through Mary. Thus the virgin birth accomplishes exactly what is necessary: Jesus is both legally and biologically the Son of David, while avoiding every imagined problem associated with Jeconiah’s immediate judgment.

The Real Significance for Mary and Joseph

Modern speculation sometimes claims Joseph’s ancestry made him socially undesirable, and that Mary would have faced stigma for marrying into a cursed line. No historical or Jewish source supports this idea. Joseph’s lineage was not considered tainted. Jewish tradition never saw his ancestry as disqualified. Mary’s marriage to Joseph fits seamlessly within normal first-century Jewish expectation. The notion that Joseph came from a disgraced family is a modern projection based on misreading Jeremiah 22. The genealogies themselves treat his line as perfectly legitimate.

Conclusion

The so-called Jeconiah problem appears only when Jeremiah 22 is removed from its context and interpreted as a permanent curse on all his future descendants. The text does not teach this. The judgment applied to Jeconiah’s own days and his immediate sons during the collapse of the monarchy. Jewish interpretation never saw his line as disqualified. The Davidic covenant remained intact. Matthew gives Jesus the legal right to the throne through Joseph. Luke establishes His biological descent from David through Mary.

The virgin birth brings these lines together so that Jesus inherits the throne of David without inheriting any judgment associated with Jeconiah. Jeremiah, Haggai, Matthew, and Luke form a unified testimony that God kept His promise. Jesus stands as the rightful Son of David whose kingdom will never end.

Discussion Questions

- How does reading Jeremiah 22:28–30 in its original historical context change the way we understand the nature and limits of the judgment pronounced on Jeconiah?

- What clues within the wording of the passage itself indicate that the curse applies to Jeconiah’s own generation rather than to all future descendants?

- How does the fall of the monarchy during the Babylonian conquest help explain the meaning behind God declaring Jeconiah “childless” in a political sense?

- Why is it important to distinguish between the Davidic covenant and the temporary judgments that fell on individual kings within David’s line?

- How does recognizing the limited scope of the Jeconiah curse help clarify the role of Jesus’ legal and biological genealogies in Matthew and Luke?

Want to Know More?

- Jesus and the Old Testament: His Application of Old Testament Passages to Himself and His Mission by R. T. France

A respected academic study explaining how Jesus and the New Testament writers used and understood Old Testament passages. France’s work helps clarify how prophetic texts functioned and how messianic identity was established. - Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels edited by Joel B. Green, Scot McKnight, and I. Howard Marshall

A widely used scholarly reference offering detailed articles on genealogy practices, messianic expectations, first century Judaism, and the background of the Gospels. This provides strong context for understanding Matthew and Luke’s genealogies. - The Birth of the Messiah by Raymond E. Brown

A comprehensive analysis of the infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke. Brown includes an extended examination of both genealogies, their structure, purpose, and how they fit within Jewish tradition. - Jesus the Messiah: A Survey of the Life of Christ by Robert H. Stein

A clear and academically reliable overview of Jesus’ life with attention to His fulfillment of Old Testament messianic promises, including the royal line of David and the meaning of kingship in Jewish thought. - The New Testament in Its World by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird

An essential introduction to the historical and theological world of the New Testament. Wright and Bird discuss Jewish royal expectations, genealogical function, and the significance of Jesus’ Davidic identity.