The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE stands as one of the most traumatic and defining moments in Jewish history. While it is often attributed to the Roman Empire, historical evidence reveals that the actual destruction was largely carried out by provincial forces—Syrians, Arabs, and other regional auxiliaries—who played the decisive role in the Temple’s devastation.

This article examines the Hebrew term עמי (‘ammi) in Daniel 9:26, arguing that the prophecy points not to the Roman Empire in general, but to specific ethnic groups who were directly responsible for burning the sanctuary. This interpretation has implications not only for historical understanding but also for future prophetic expectations.

The Biblical Prophecy: Daniel 9:26

“And after threescore and two weeks shall Messiah be cut off, but not for himself: and the people of the prince that shall come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary…” (Daniel 9:26, KJV)

This passage has traditionally been interpreted to mean that the Romans—acting as “the people of the prince that shall come”—destroyed the city of Jerusalem and the Temple. However, a closer look at the term “people” reveals a more precise meaning that warrants reexamination.

The Hebrew Term עמי (‘ammi) and Its Meaning

The word עמי (‘ammi) is often translated simply as “people,” but in Biblical Hebrew, it carries a strong ethnic connotation. It typically refers to a specific group united by shared ancestry, language, or cultural identity. For instance, ‘Ammi Yisrael (My people Israel) is a covenantal term identifying the nation of Israel, not just a mass of individuals or imperial subjects.

When applied to Daniel 9:26, this distinction is critical. The phrase “the people of the prince that shall come” refers to a defined ethnic group or groups—not a generic imperial force. This reading aligns with historical records that identify those who physically destroyed the Temple not as ethnic Romans from Italy, but as provincial auxiliaries embedded in Rome’s eastern legions.

Josephus: The Role of the Provincial Forces

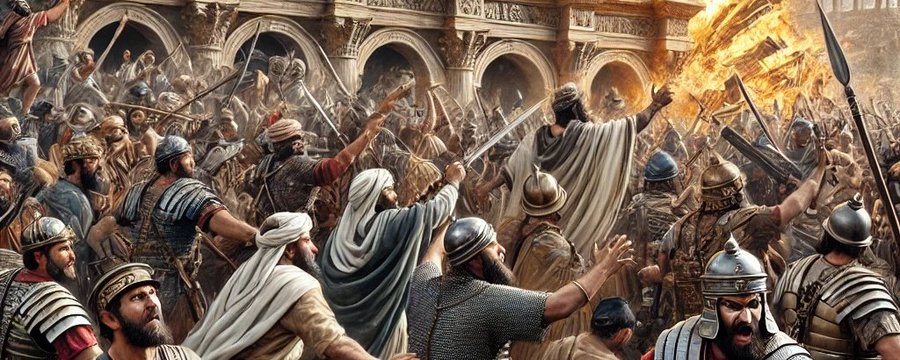

Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, is explicit in stating that Titus, the Roman general commanding the siege of Jerusalem, ordered the Temple to be spared. The destruction occurred in defiance of his orders.

“But Titus said that, although the Jews should lay the temple even with the ground, he would not do it himself; and when one of those who were with him advised him to destroy it, he said, ‘No, by the gods, not while I am alive. When it is gone, where shall I ever get another such work?’”

— The Jewish War 6.4.3 (Whiston translation)

Josephus also records that Titus rushed to the scene and tried to stop the fire once it was set, but the soldiers—fueled by rage and a deep-seated hatred of the Jews—ignored his commands.

“Titus came in haste and commanded the soldiers to quench the fire. He was yet unable to restrain the fury of the soldiers; their anger and hatred toward the Jews, along with the noise and confusion, prevented his commands from being obeyed. Moreover, many believed that Titus had actually ordered the Temple to be burned.”

These provincial soldiers—particularly Syrians and Arabs—acted out of ethnic hostility rather than disciplined military obedience. Josephus emphasizes that their actions were not part of a Roman imperial strategy but were driven by long-standing regional hatred and vengeance.

Tacitus: Ethnic Composition of the Legions

Tacitus, the Roman historian, also provides important evidence. In The Histories (Book 5), he outlines the composition of the legions involved in the siege. The legions were primarily drawn from the eastern provinces, especially Syria, with notable contingents of Arabs and other non-Roman elements.

These provincial soldiers were not Roman citizens from the Italian peninsula, but rather conscripts and volunteers from client kingdoms and Roman territories. Their religious and ethnic backgrounds made them more inclined to despise the Jews and to act violently during the siege. Tacitus’s observations corroborate Josephus’s narrative and add Roman confirmation of the ethnic identities involved.

Theological and Prophetic Implications

This ethnically grounded interpretation of ‘ammi has far-reaching consequences for both theology and eschatology. If the “people of the prince” were Syrians and Arabs rather than ethnic Romans, then the prophecy in Daniel 9:26 is not about a generalized Roman future but about the descendants or ideological heirs of those specific ethnic groups.

This reframes expectations of the “prince who is to come.” It casts serious doubt on interpretations that assume the Antichrist must emerge from a revived European Roman Empire. Instead, it opens the door to alternative readings—such as the possibility that the Antichrist arises from a revived Islamic Caliphate, rooted in the same ethnic and religious identities that destroyed the Temple.

Conclusion

A closer examination of the Hebrew term עמי (‘ammi) in Daniel 9:26 reveals that the prophecy points to ethnic groups—specifically Syrians, Arabs, and other provincial forces—rather than the Roman Empire as a whole. Historical evidence from Josephus and Tacitus confirms that these groups, not the Roman command, were responsible for the destruction of the Second Temple.

Recognizing this ethnic identity reshapes how we read the prophecy and what we expect in future fulfillment. It challenges long-standing eschatological assumptions and refocuses attention on the Middle East—not Rome—as the key region to watch in the unfolding of biblical prophecy.

Discussion Questions

- How does the ethnic reading of ‘ammi in Daniel 9:26 reshape traditional interpretations of this prophecy?

- What do the accounts of Josephus and Tacitus reveal about the true perpetrators of the Temple’s destruction?

- Why would provincial forces like Syrians and Arabs have had more motivation to destroy the Temple than Roman citizens?

- How does this interpretation affect popular eschatological views that place the Antichrist in a revived Roman Empire?

- What are the implications of this historical evidence for understanding the future restoration of an Islamic empire in prophecy?

Want to Know More?

- Josephus, The Jewish War (translated by William Whiston)

A firsthand account of the siege of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple, including Titus’s desire to spare the Temple and the disobedience of the provincial troops. - Tacitus, The Histories and The Annals (translated by A. J. Church and W. J. Brodribb)

Offers a Roman perspective on the events surrounding the Jewish War, with specific reference to the role of Syrians and Arabs in the eastern legions. - Joel Richardson, Mideast Beast: The Scriptural Case for an Islamic Antichrist

Argues for a Middle Eastern origin of the Antichrist and explores the ethnic, political, and religious dynamics that align with Daniel 9:26 and other prophetic texts. - W. H. C. Frend, Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church

While focused on Christian suffering, this book explores the attitudes of eastern provincial populations toward Jews and Christians, reinforcing the ethnic tension in the region. - Stephen Dando-Collins, Conquering Jerusalem: The AD 66–73 Roman Campaign to Crush the Jewish Revolt

This book gives a detailed and historically grounded account of the Roman campaign that culminated in the destruction of the Second Temple, including the composition and actions of the forces involved.