At the heart of Orthodox Christianity lies a profoundly sacramental vision of reality, one in which worship does not merely recall past events or anticipate future fulfillment but draws the faithful into the living presence of God. Orthodox spirituality understands the Church’s rites as encounters with eternity, moments where heaven and earth overlap and the constraints of ordinary time are set aside. This conviction shapes the entire liturgical life of the Church, from the Divine Liturgy to the veneration of relics, both of which testify to the belief that the Kingdom of God is not only awaited but actively entered through worship.

Orthodoxy does not treat sacred rites as symbolic gestures meant to stimulate memory or emotion. Instead, the Church understands worship as participation in divine realities that exist beyond chronological time. When believers gather, they are not reenacting sacred history but stepping into it. This perspective is grounded in the biblical distinction between chronos, measured and sequential time, and kairos, the appointed moment of God’s decisive action. In Orthodox worship, kairos breaks into chronos, allowing the faithful to encounter the eternal now of God’s kingdom.

Liturgical Time and the Reality of Kairos

The Orthodox Church views liturgical time as fundamentally different from ordinary time. While daily life moves forward in linear progression, the liturgy unfolds as an entry into God’s eternal present. This is why Orthodox services are saturated with language that collapses past, present, and future into a single act of worship. The Church does not merely remember Christ’s saving work but proclaims it as a present and active reality.

This understanding is deeply rooted in Scripture, particularly in passages that describe heavenly worship as ongoing and unceasing. The book of Revelation does not portray heaven as waiting for history to conclude before worship begins. Instead, it reveals a realm where praise is already underway and where redeemed humanity already stands before God, even while the full restoration of all things is not yet complete. Orthodox worship understands itself as a participation in that same heavenly liturgy, not a symbolic imitation of it.

The Divine Liturgy as Heavenly Worship

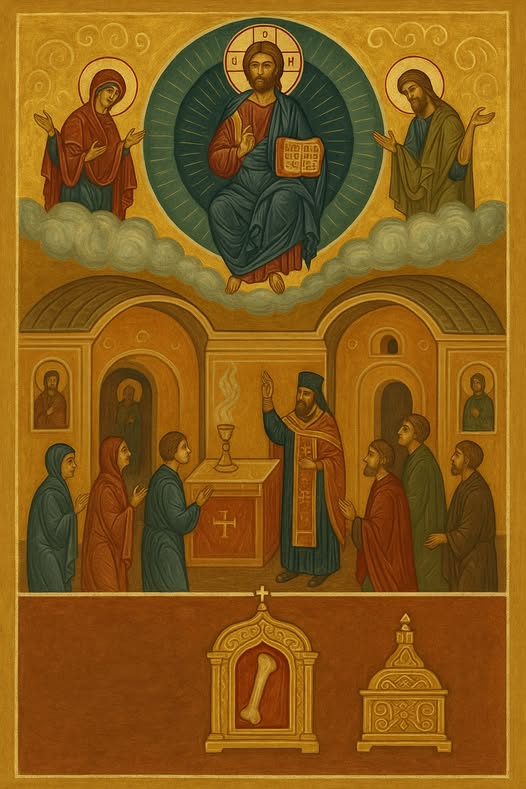

Nowhere is this eternal perspective more fully expressed than in the Divine Liturgy, the central act of Orthodox worship. The Liturgy is not approached as a service observed from a distance but as an act in which the faithful actively participate. The Church gathers with the conviction that it stands before God alongside the angels and the saints, offering praise that transcends earthly limitations.

This is why Orthodox churches are intentionally designed to reflect heaven rather than accommodate modern efficiency. Icons, incense, chant, and ritual movement are not aesthetic additions but theological statements. They proclaim that worship is not confined to the material world and that the senses themselves are drawn into the experience of eternity. When the Liturgy begins, the Church does not imagine heaven but enters into its worship.

The Eucharist and the Eternal Sacrifice of Christ

At the heart of the Divine Liturgy stands the Eucharist, which most clearly embodies the Orthodox understanding of time and eternity. The Eucharist is not treated as a symbolic reminder of Christ’s sacrifice, nor as a repetition of it. Orthodox theology holds that Christ’s sacrifice is once for all, complete and unrepeatable, yet eternally present before the Father.

In the Eucharist, the Church is brought into that eternal offering. The faithful do not travel back in time to the Last Supper, nor do they merely recall the crucifixion and resurrection. Instead, they participate in the timeless reality of Christ’s self-offering, which stands outside historical sequence. This is why the Eucharist is spoken of as a mystery, not because it is vague or irrational, but because it transcends the categories of ordinary experience.

The Communion of Saints Beyond Time

The Orthodox understanding of worship also reshapes the Church’s view of the communion of saints. The Church is not divided between the living and the departed, nor fractured by centuries of history. All who are in Christ are alive in Him, and all worship together as one body. This unity is not poetic language but a lived reality expressed every time the Church gathers for prayer.

In Orthodox services, the saints are not treated as distant figures from the past but as present members of the worshiping community. Their hymns are sung, their intercessions are invoked, and their lives are held up as evidence that the victory of Christ over death is already at work. This reinforces the conviction that the Church’s worship transcends time and that believers participate in a fellowship that stretches across centuries without losing its unity.

Relics as Witnesses to the Eternal Kingdom

The veneration of relics flows naturally from this understanding of time and eternity. Relics are not honored as historical curiosities or sentimental connections to the past. They are revered as tangible witnesses to the reality of resurrection and the transformation of the human person through union with Christ.

Orthodox Christianity affirms that salvation involves the whole person, body and soul. The saints are not disembodied spirits awaiting redemption but glorified members of Christ’s body whose lives testify to the sanctification of creation itself. Relics bear witness to this truth by proclaiming that holiness is not abstract or purely spiritual but leaves its mark on the physical world.

Relics and Sacred Space

The placement of relics within Orthodox churches further reinforces their theological significance. Altars are traditionally consecrated with relics, reflecting the early Christian practice of celebrating the Eucharist over the graves of martyrs. This practice proclaims that the Church’s worship is inseparable from the witness of those who have already finished the race.

Relics also sanctify sacred space by declaring that heaven and earth meet within the Church. They remind the faithful that death has been defeated and that the resurrection is not merely a future hope but an already unfolding reality. Through the presence of relics, the Church visibly confesses its belief in the ultimate restoration of creation and the bodily resurrection of the faithful.

Conclusion

The transcendent nature of Orthodox worship and the veneration of relics together offer a vision of faith rooted in participation rather than observation. The sacred rites of the Church are not educational tools designed to convey information about God. They are encounters with God Himself, drawing believers into communion with Christ, the saints, and the heavenly host.

In Orthodox Christianity, worship is not confined to the flow of ordinary time. It is an entry into eternity, a foretaste of the age to come. Through the Divine Liturgy, the Eucharist, and the veneration of relics, the faithful are invited to step beyond the limits of the temporal world and into the living reality of God’s kingdom, where death is overcome and worship never ends.

Discussion Questions

- How does the Orthodox understanding of worship as participation in eternity challenge modern assumptions that worship is primarily symbolic or commemorative?

- In what ways does the distinction between chronos and kairos help explain how the Divine Liturgy brings past, present, and future together in a single act of worship?

- How does Revelation’s portrayal of ongoing heavenly worship shape the Orthodox view of the Church’s worship on earth as part of an already but not yet reality?

- Why is the veneration of relics consistent with the Orthodox belief in bodily resurrection and the sanctification of the material world, rather than a distraction from Christ?

- How might viewing worship as a foretaste of the age to come change the way believers approach the Divine Liturgy, the Eucharist, and participation in the life of the Church?

Want to Know More

- Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church

A foundational introduction to Orthodox Christianity that explains the Church’s theology, worship, and sacramental worldview. Ware provides essential background for understanding why Orthodoxy views liturgy as participation in heavenly reality rather than symbolic remembrance. - Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World

A classic work on Orthodox sacramental theology that explores how worship, especially the Eucharist, reveals the true nature of creation and humanity’s calling. Schmemann’s emphasis on the Eucharist as entry into the Kingdom directly informs the article’s treatment of liturgical time and eternity. - Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church

A theological exploration of Orthodox spirituality that emphasizes mystery, participation, and the experiential knowledge of God. Lossky’s work is particularly important for understanding why Orthodox theology resists reducing worship to rational explanation or symbolism. - John D. Zizioulas, Being as Communion

A major theological work that examines personhood, communion, and the Church’s existence as participation in divine life. Zizioulas provides a strong theological framework for the communion of saints and the Church’s unity across time and death. - John Behr, The Mystery of Christ: Life in Death

A patristically grounded study of Christ’s death and resurrection and how they are lived out in the Church’s worship. Behr’s work helps illuminate the Orthodox understanding of the already but not yet reality of salvation and eternal life.