The Bible was never meant to be locked behind an elite priesthood or preserved in a single language. It began in the languages of ordinary people—Hebrew for the tribes of Israel, Aramaic for a people in exile, and Greek for a world ruled by empire. These were the living tongues of the marketplace, the courtroom, the synagogue, and the home. From the very beginning, the Scriptures were meant to be heard and understood by those who walked the dusty roads of Judea and Galilee. The prophets did not speak in riddles; they cried out in the language of their people, demanding repentance and pointing to the promises of God.

How Bible Translation Actually Works

One of the most persistent myths about Bible translations is that modern versions are just layered translations, with English Bibles supposedly translated from Latin, which was translated from Greek, which was translated from Hebrew, and so on. This idea paints a picture of corruption through repeated reinterpretation, as though the Bible we read today is a blurred echo of the original. That is simply not how the process works.

Faithful Bible translation is not a game of telephone. Nearly every serious modern translation is produced by teams of scholars who work directly from the best available manuscripts in the original languages: Hebrew and Aramaic for the Old Testament, and Greek for the New Testament. These scholars are experts not only in biblical languages, but also in the cultures, idioms, and literary forms of the ancient Near East and the Greco-Roman world.

The process begins with textual criticism, the science of comparing thousands of ancient manuscripts to reconstruct the original wording as accurately as possible. While no original manuscripts survive, the vast number of copies, many of them very early, allows scholars to identify and correct scribal errors, insertions, or alterations that occurred over centuries of copying. These critical editions form the base text from which translators work.

Once the original-language text is established, translators begin the careful task of rendering it into contemporary language. This is not mechanical word-swapping. It involves deep decisions about grammar, syntax, tone, metaphor, cultural context, and theological nuance. Translators must constantly balance accuracy, clarity, and faithfulness, knowing that every word choice can influence interpretation. Some teams lean toward a more literal approach, preserving sentence structure and word order. Others aim to convey meaning more fluidly, adapting ancient expressions to modern idioms.

Most reputable translations are not the product of a single person but of committees representing diverse theological backgrounds, with multiple rounds of peer review, revision, and annotation. Notes are often included to show where alternate readings or translation options exist. This transparency protects the integrity of the translation and allows readers to explore deeper layers of meaning.

What this means is simple: modern Bible translations are not built on a chain of secondary sources. They go back to the earliest and most reliable manuscripts available. The work is slow, deliberate, and accountable. And while no translation is perfect, the idea that today’s Bibles are copies of copies of copies is a myth that does not hold up under scrutiny.

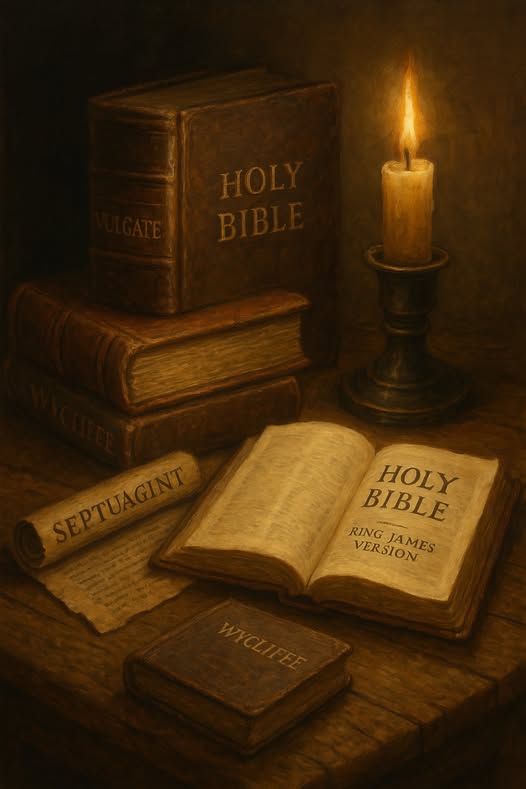

The Septuagint: Crossing the First Barrier

When the Jewish people were scattered and Hellenized under Greek rule, a problem arose. Many could no longer read the Hebrew Scriptures. In response, a group of Jewish scholars in Alexandria began translating the Hebrew Bible into Greek. This work became known as the Septuagint. It was more than a linguistic exercise—it was a declaration that God’s Word must be accessible. Early Christians embraced it, and New Testament authors quoted from it freely. But the Septuagint also introduced new interpretive nuances. It became not just a translation but a lens through which messianic prophecies were understood in a world rapidly shifting toward the gospel of Christ.

Jerome and the Vulgate: The Word Bound in Latin

As Latin became the dominant language of the Western world, the Church needed a Bible that would match its administrative and theological unity. Jerome answered that call in the fourth century, translating the Old Testament directly from Hebrew and the New Testament from Greek into Latin. His translation, known as the Vulgate, would become the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church for over a thousand years. At first, it was a gift to the people. But as Latin faded from everyday speech and became the language of the clergy, the Bible slipped out of the hands of the congregation. What began as an effort to clarify soon became a means of control.

The Underground Flame: Wycliffe, Hus, and the Cry for Access

In medieval England, John Wycliffe dared to challenge the belief that only the Church hierarchy could interpret Scripture. He held that the Bible was the highest authority for doctrine and life, not the pope, not the councils, and not tradition. This conviction led him to translate the Scriptures from the Latin Vulgate into Middle English, a bold act at a time when possessing or distributing vernacular copies was considered heresy. Though his translation was not based on the original Hebrew or Greek, it made the Word of God understandable to the common people for the first time in generations.

Wycliffe’s followers, known as the Lollards, took up his vision. They copied his translation by hand, memorized large portions of it, and spread it through underground networks. For this, they were hunted, arrested, tortured, and burned. The Church declared that these unauthorized translations would lead to confusion, error, and heresy. It was officially argued that the Bible in the hands of untrained laypeople would be dangerous, that vernacular languages were unstable and unworthy of sacred truth, and that only the Church had the authority to interpret Scripture. These claims were formalized in Church policy. The Council of Toulouse in 1229 explicitly forbade laypeople from possessing books of the Bible in the vernacular. Just a few years later, the Council of Tarragona in 1234 ordered all Romance-language Bibles to be surrendered and burned.

While the stated concern was doctrinal purity and protection against heresy, the consistent suppression of access reveals the deeper motive. If ordinary believers could read the Word for themselves, they would see how far the institution had drifted from it, and the Church would lose its tight control over teaching and power.

In Bohemia, Jan Hus echoed Wycliffe’s message. He preached in the language of the people and condemned the corruption of the clergy. He declared that Christ alone, not the pope, was the head of the Church, and he urged the people to test every teaching by the Word of God. For this defiance, he was excommunicated, lured to a false trial under a promise of safe conduct, and burned at the stake. His final words were a prophecy: “You may kill a goose, but in a hundred years, a swan will arise.” That swan would come in the form of Martin Luther.

These men were not simply critics of the Church; they were witnesses to a higher authority. They believed that God’s Word was not the possession of the powerful, but the inheritance of every soul. Their sacrifices lit the first sparks of a fire that would soon engulf Europe and forever alter the course of Christian history.

The Reformation and the Language of the People

That firestorm came with the Protestant Reformation. Central to its message was a return to Scripture, and not just for theologians, but for every soul. Reformers insisted that the Bible was not the property of popes and priests, but the inheritance of the Church universal, made up of all believers. If the Word of God was to be the ultimate authority, it had to be heard and understood by the people in their own tongue.

Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible into German marked a turning point. He did not work from the Latin Vulgate, but returned directly to the Hebrew and Greek texts. His goal was not only linguistic accuracy but pastoral clarity. He wanted a plowboy to understand the Psalms and the letters of Paul as easily as a scholar. His translation became a national event in Germany, fueling both religious reform and the development of the modern German language itself. For many, it was the first time they had encountered Scripture firsthand rather than filtered through a homily in Latin.

Meanwhile, William Tyndale brought this same vision to the English-speaking world. His New Testament, published in 1526, was translated directly from the Greek and printed using the newly available printing press. It was small enough to smuggle and cheap enough to share. Tyndale’s bold aim was clear: he once told a critic that if God spared his life, he would see to it that a boy driving a plow would know more of the Scriptures than the pope. The Church saw this as insubordination. For his efforts, he was betrayed, imprisoned, strangled, and burned.

Yet his work could not be undone. Tyndale’s phrasing, clarity, and theological precision formed the backbone of nearly every subsequent English Bible. When the King James Version was published nearly a century later, upwards of eighty percent of its New Testament phrasing followed Tyndale almost word for word. His translation endured because it was faithful, beautiful, and readable. Through his sacrifice, the English Bible became not just a book but a movement, one that forever changed the religious landscape of the English-speaking world.

The work of Luther and Tyndale was not just about language; it was about lordship. It challenged the very foundation of spiritual authority and put the Word of God directly into the hands of the people. In doing so, it shattered centuries of ecclesiastical control and called Christians back to the voice of their Shepherd.

The King James Bible and the Politics of Translation

Commissioned in 1604 by King James I of England and completed in 1611, the King James Version (KJV) was born out of both theological ambition and political necessity. The goal was to unify competing factions within the English Church and to replace earlier Protestant Bibles like the Geneva Bible, whose marginal notes were viewed as subversive. The translators worked from the best Hebrew and Greek manuscripts available to them at the time, particularly the Masoretic Text and the Textus Receptus. While they translated directly from the original languages, they also consulted earlier English versions, especially William Tyndale’s pioneering work, whose phrasing often proved so precise and elegant that it was preserved almost verbatim.

The result was a literary masterpiece shaped by the rhythms of Elizabethan English and the theological tensions of the Reformation age. It stood not only as a translation but as a cultural monument, deeply shaping English-speaking Christianity for centuries. Yet the translators themselves did not consider their work untouchable. In the preface to the reader, they acknowledged that all translations are subject to improvement and correction. They did not claim final authority for their version, but rather saw it as part of a living tradition of faithfulness to the Word. They expected that future discoveries, better manuscripts, and deeper understanding would one day refine their work. That spirit of humility stands in stark contrast to the later insistence by some that the King James Version alone is divinely preserved or beyond revision.

Though based on a more limited manuscript tradition than what is available today, the KJV remains a towering achievement. But its greatness lies not in claims of perfection, but in its clarity, reverence, and lasting influence. It opened the Bible to millions, and in doing so, advanced the same goal shared by the reformers before it: that God’s Word might be heard plainly and truly by all people.

New Discoveries and the Rise of Modern Translations

In the centuries that followed the Reformation, translation efforts continued, but it was not until the modern era that a new wave of versions truly reshaped the landscape. Beginning in the 19th and accelerating in the 20th century, archaeological discoveries and advances in textual criticism transformed how scholars approached the biblical text. These developments offered access to manuscripts far older than those available to the King James translators, shedding new light on the original words of Scripture.

In the realm of the New Testament, older Greek manuscripts began to emerge that predated those used by Erasmus and the compilers of the Textus Receptus. Codices such as Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, along with numerous papyri, revealed small but important differences in wording and order. These variants involved things like spelling, word arrangement, and the occasional omitted phrase, but they didn’t alter any central doctrine of the Christian faith. For instance, many newer translations either bracket or omit later additions like the longer ending of Mark or the story of the woman caught in adultery, not out of irreverence, but because those passages do not appear in the earliest and most reliable manuscripts. These decisions are made transparently and reflect a commitment to accuracy rather than innovation.

In the realm of the New Testament, older Greek manuscripts began to emerge that predated those used by Erasmus and the compilers of the Textus Receptus. Codices such as Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, along with numerous papyri, revealed small but important differences in wording and order. While these variants rarely affected central doctrines, they required translators to reevaluate certain verses. For instance, many newer translations either bracket or omit later additions like the longer ending of Mark or the story of the woman caught in adultery, not out of irreverence, but because those passages do not appear in the earliest and most reliable manuscripts.

These discoveries led to a renewed sense of responsibility in translation. Some modern versions, like the Revised Standard Version, the New American Standard Bible, and the English Standard Version, sought to retain as much of the original structure and phrasing as possible while updating archaic vocabulary. Others, like the New International Version and the Christian Standard Bible, aimed for clarity and readability without straying far from the original intent. In both cases, the translators returned to the ancient sources, not previous translations, and worked in teams to ensure theological balance and scholarly integrity.

Yet the modern era also saw the rise of paraphrases and interpretive renderings that blurred the line between translation and commentary. Versions like the New Living Translation, though rooted in solid scholarship, often reword complex phrases to suit contemporary language. Others, like The Message, present Scripture more as devotional literature than precise translation. While these can serve as helpful supplements, they sometimes replace the text itself in the minds of readers, creating a distance from the original language and ideas.

The tension between accuracy and accessibility now defines almost every translation project. There is no perfect Bible version, but there are faithful ones. Each choice reflects priorities, whether literary form, theological clarity, or reader comprehension. What matters is not just what the text says, but whether the reader is being invited to engage with the Word of God in a way that is honest, reverent, and grounded in the best understanding of what was written so long ago.

When Translation Becomes Distortion

Not every translation effort has honored the integrity of the text. Some have gone far beyond clarifying language and ventured into rewriting Scripture to suit theological agendas, personal visions, or sectarian beliefs. These are not simply poor translations—they are deliberate distortions.

One example is The Passion Translation, a paraphrase marketed as a fresh revelation of God’s Word, yet produced by a single individual who claims supernatural insight into ancient languages without formal training. It regularly adds phrases, injects charismatic theology into texts where it does not exist, and stretches words well beyond their textual meaning. It is not a translation in any meaningful sense, and its popularity in some circles speaks more to emotional appeal than to fidelity to Scripture.

Equally problematic is the New World Translation, the official Bible of Jehovah’s Witnesses. It deliberately mistranslates key Christological texts, most famously rendering John 1:1 as “the Word was a god” in contradiction to the rules of Greek grammar and nearly every scholarly translation in existence. The goal is clear—to strip Jesus of His divinity and reshape the Bible to reflect the theological positions of the Watchtower Society. This is not a difference in interpretation; it is an intentional alteration of the original text.

The Joseph Smith Translation, used within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, follows yet another path. Rather than translating from Hebrew or Greek, Joseph Smith claimed authority to revise the King James Version by revelation. In doing so, he inserted entire theological frameworks foreign to the biblical narrative. Verses were expanded, invented, or reversed to reflect early Mormon doctrine. Despite lacking manuscript support or linguistic basis, the JST is still used devotionally and doctrinally by many Latter-day Saints.

Even more mainstream paraphrases, like The Message, blur the line between translation and commentary. While not deceitful in intent, its heavy rewording of the text and tendency to interpret rather than translate makes it unsuitable for teaching or theology. The danger lies in how easily a paraphrase can become a person’s only exposure to the Bible, giving them not Scripture, but one man’s retelling of it.

These versions remind us that not everything labeled a “Bible” carries the voice of Scripture. When translators claim authority higher than the text or adjust God’s Word to fit their worldview, they cease to translate and begin to replace. At that point, the reader is no longer hearing God—they are hearing man.

Conclusion

The history of Bible translation is not a history of innovation for its own sake. It is a story of resistance to spiritual gatekeeping. From the scholars of Alexandria to the reformers who died at the stake, from scribes in candle-lit monasteries to coders and linguists today, one theme remains constant: God’s Word will reach His people. It cannot be stopped. Language changes. Empires fall. Technology evolves. But the voice that once thundered from Sinai and whispered in Galilean hills still speaks—and thanks to centuries of translation, it speaks in every corner of the world.

Discussion Questions

- Why was translating the Bible into the language of the people seen as such a threat by religious and political authorities?

- How did the source texts chosen for translation (Hebrew, Greek, Latin) affect the final message and interpretation?

- What are the dangers of paraphrased or agenda-driven translations like The Passion Translation or the New World Translation?

- How did technological advancements like the printing press and Bible apps change access to Scripture?

- What criteria should be used when choosing a Bible translation for serious study or teaching?

Want to Know More?

- Bruce M. Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions

A comprehensive yet accessible guide to major Bible translations throughout history, written by one of the foremost scholars in textual criticism. - Leland Ryken, Understanding English Bible Translation: The Case for an Essentially Literal Approach

Explains the philosophy behind formal equivalence and why accurate translation matters, especially in preserving theological clarity. - Adam Nicolson, God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible

A vivid historical narrative that captures the political, literary, and religious forces behind the creation of the King James Version. - Robert Alter, The Art of Bible Translation

A seasoned translator and literary critic reflects on the challenges of conveying Hebrew’s stylistic nuance without sacrificing accuracy. - Mark Ward, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible

Tackles modern debates about the KJV with clarity and respect, showing why understanding translation choices still matters today.