The ancient world was filled with gods, gods of cities, storms, rivers, fertility, and war. And with these gods came prophets, those who claimed to speak on their behalf. In the biblical worldview, these were not simply mythical figures or cultural symbols. They were real spiritual beings, elohim, some of whom had been given temporary authority over the nations (Deuteronomy 32:8–9), while others seized what was never theirs to begin with. All had rebelled against Yahweh. Their prophets were not neutral religious figures. They were the mouthpieces of defiance, calling people to serve created beings instead of the Creator.

These prophets were embedded in the royal courts and temples of Mesopotamia, Canaan, Egypt, and beyond. They delivered oracles, sanctioned wars, interpreted signs, and enforced the will of the gods they served. But they did not serve gods of equal standing to Yahweh. They served beings under judgment, spiritual powers who had traded truth for worship, and their prophets advanced their corrupted agendas.

What These Prophets Did

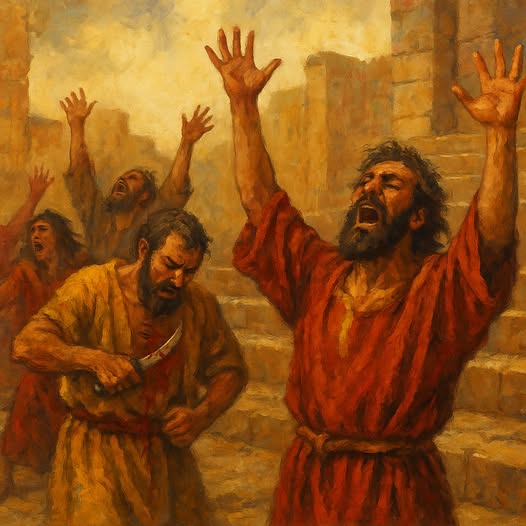

Unlike the prophets of Yahweh, the prophets of other gods operated through performance, manipulation, and ritual spectacle. In Mesopotamian cities like Mari, prophets who served deities such as Ishtar or Shamash entered ecstatic trances. They would shout cryptic messages or perform strange, dramatic gestures, signs of supposed divine possession. These displays were intended to signal that the gods were speaking, not through truth, but through overwhelming sensory expression.

The Canaanite prophets, particularly those loyal to Baal, were notorious for their frenzied rituals. At Mount Carmel, the prophets of Baal cried out, slashed themselves, and danced with wild intensity in a desperate attempt to force Baal to respond (1 Kings 18:26–29). Their entire system was transactional. If humans gave enough blood, devotion, and rituals, they believed they could manipulate divine forces into acting on their behalf.

These prophets were not fringe figures. They operated in official capacities, closely tied to the power structures of their nations. Kings relied on them to validate wars, interpret omens, and ensure divine favor. But they were not conduits of revelation. They were agents of allegiance, reinforcing loyalty to spiritual beings who had rebelled against Yahweh.

Prophets of the Rebellious Gods vs. Yahweh

Scripture never presents these gods or their prophets as equals to Yahweh or His messengers. These were created beings, at times permitted limited influence, at other times seizing territory through deception. But they were never sovereign. Their prophets functioned as collaborators in rebellion, not rivals in truth.

At Mount Carmel, Elijah’s showdown with the prophets of Baal was more than a theological debate. It was a public unveiling of impotence. Baal’s prophets raged for hours, cutting themselves and crying out. But no fire fell. No voice answered. Then Elijah prayed once, and fire from heaven consumed the offering, the wood, the altar, and even the water in the trench. Yahweh had no need of theatrics. His authority was absolute.

Though the Bible does not detail the prophets of the Philistines, it is reasonable to assume that figures spoke on behalf of Dagon and other regional gods during military conflicts. Yet in 1 Samuel 5, Dagon is found shattered before the ark of Yahweh, his statue broken, his hands and head removed. It was a visual prophecy. This god had no power before the presence of Israel’s God.

A clearer historical window into the world of foreign prophecy is found in the Moabite Stone (Mesha Stele), which records King Mesha crediting Chemosh for victories against Israel. The inscription reveals a religious worldview where national success was credited to divine favor. This implies the existence of prophets and priests of Chemosh, tasked with interpreting such victories and reinforcing devotion to the god of Moab.

The biblical account in 2 Kings 3 tells a darker version. Israel, Judah, and Edom form a coalition to attack Moab. They push the Moabites back to their capital, and then the unimaginable happens. King Mesha, in a final act of desperation, sacrifices his firstborn son on the city wall. The horror is immediate and effective. “There came great wrath against Israel, so they withdrew.” Scholars have long debated what exactly happened, but from a biblical worldview, it is possible the Israelites believed the sacrifice had unleashed demonic power. They were not materialists. They knew the gods of the nations were real spiritual entities. And in that terrifying moment, their courage failed.

The prophets of Chemosh may have proclaimed this as a glorious act. But what it revealed was the true nature of the god they served. Chemosh demanded the blood of a child. Yahweh, by contrast, had already shown at Carmel and throughout Israel’s history that He needed no such sacrifice to act. The difference between them could not have been more stark.

The Role of These Prophets in Israel’s Apostasy

Israel was not ignorant of the danger these prophets posed. Deuteronomy 13 warned that even if a prophet performed signs or wonders, if they led the people to serve other gods, they were to be rejected and put to death. The test was not power. It was loyalty. Yahweh had revealed Himself through deliverance from Egypt, covenant at Sinai, and provision in the wilderness. No other god could lay that claim.

Yet Israel repeatedly turned away. The appeal of Baal and Asherah was not just theological. It was political, sexual, agricultural, and national. These gods promised fertility, victory, and protection, and their prophets stood ready to offer divine endorsement. They made rebellion seem righteous and idolatry seem logical. Often, they operated within Israel’s borders, offering a diluted spirituality that required no holiness and no covenant faithfulness.

Yahweh’s prophets were sent to confront them, not to coexist. Elijah, Elisha, Jeremiah, and others stood alone, ridiculed, hunted, and hated because they called Israel back to the God who made them. When the people refused to listen, judgment came. The prophets of other gods were cast down, their temples destroyed, their names forgotten.

Conclusion

The prophets of the nations were not part of a pluralistic tapestry of truth. They were not misunderstood seekers or alternate paths to the divine. They were emissaries of rebellion. They served spiritual powers under judgment, whose only hope was to steal worship from Yahweh and draw humanity into their doom.

The biblical prophets stood against this, not just with words but with fire, famine, signs, and suffering. They were not debating. They were calling for allegiance. The question was never, “Which god is more powerful?” The question was, “Will you remain loyal to the God who made you, or follow the voices of beings already condemned?”

Discussion Questions

- Why is it important to distinguish between false prophets within Israel and prophets of other gods in the surrounding nations?

- How does the story of Elijah and the prophets of Baal illustrate the fundamental difference between Yahweh and the rebellious elohim?

- What does the Moabite king’s sacrifice of his son reveal about the nature of Chemosh and the spiritual deception at play?

- In what ways did Israel’s fear of perceived spiritual power lead them to retreat or compromise, and how does that still apply to the Church today?

- How should understanding the existence of rebellious spiritual beings shape our view of ancient idolatry and modern spiritual warfare?

Want to Know More?

- Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (DDD), 2nd Edition

This essential academic reference work includes detailed entries on Chemosh, Baal, Dagon, Asherah, and other figures relevant to the ancient world of prophetic religion. Each entry includes references to ancient texts, inscriptions (like the Mesha Stele), and biblical contexts, making it invaluable for understanding how these rebellious beings functioned in the ancient Near East. - John Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament

A comprehensive introduction to ANE worldview, this book explains the background of prophecy, divine authority, and religious practices, contrasting them with the biblical view of Yahweh. - K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing

A deep dive into how kings like Mesha used propaganda and divine claims to justify war. Helps explain the theological clash between Chemosh and Yahweh in 2 Kings 3. - Daniel Block, The Gods of the Nations: Studies in Ancient Near Eastern National Theology

This book outlines how national gods were believed to rule territories through divine appointment or seizure, and how their prophets played roles in politics and warfare. - Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible

A powerful theological overview that helps explain Deuteronomy 32, the divine council, and the rebellion of the gods. Essential for framing biblical prophecy in cosmic context.