The early chapters of Exodus set the stage for one of the greatest confrontations in Scripture: Yahweh versus Pharaoh, the God of Israel against the supposed god-king of Egypt. Yet in the middle of this story, there is a surprising detail. In Exodus 4:16, Yahweh tells Moses that he will be “as elohim” to Aaron, and in Exodus 7:1, He says that Moses will be “elohim to Pharaoh.” These passages are easily overlooked, but they reveal much about divine authority, prophetic order, and the way God uses human representatives to accomplish His purposes.

Elohim in Context

The Hebrew word elohim is usually translated “God,” but it is broader than that. It refers to any inhabitant of the spiritual realm, whether Yahweh Himself, members of His heavenly council, or rebel powers. When applied to Moses, the word does not mean that he became a deity. Instead, it signifies that Yahweh appointed him to function as His direct representative, invested with divine authority for his mission. This was not about Moses’ inherent nature but about the role he was commissioned to play before both Israel and Egypt.

Moses as Elohim to Aaron

Moses was hesitant to speak, fearing that his lack of eloquence would hinder his task. Yahweh responded by appointing Aaron as Moses’ spokesman. The structure is striking. Moses would receive Yahweh’s words, then communicate them to Aaron, who would in turn speak to the people and to Pharaoh. Aaron is explicitly described as a prophet to Moses, while Moses stands in the role of elohim to Aaron.

The chain of communication looks like this: Yahweh to Moses, Moses to Aaron, and Aaron to the wider audience. This mirrors the divine-prophet relationship found throughout Scripture, where a prophet does not invent his own message but speaks the words of the god he serves. Moses therefore stands in a unique place, modeling Yahweh’s authority for Aaron.

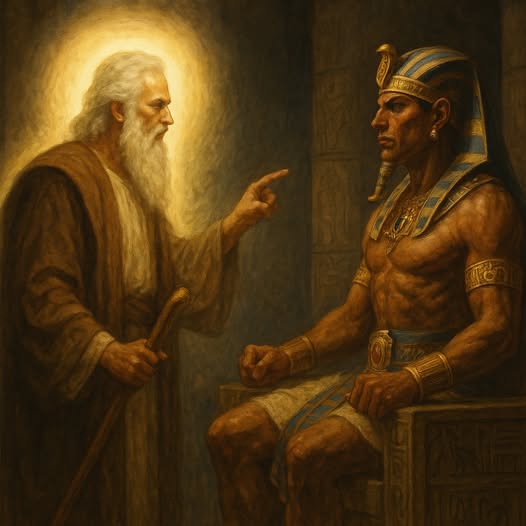

Pharaoh as Demigod, Moses as Elohim

The claim that Moses would be elohim to Pharaoh takes on even greater meaning when read against Egyptian ideology. Pharaoh was not merely a political ruler but was considered divine, the son of Ra or Horus on earth. In this way, Pharaoh occupied a role similar to the Nephilim of Genesis 6, figures remembered as half divine and half human. He was understood as a god-man, a demigod whose supposed divinity gave him the right to rule.

By calling Moses elohim to Pharaoh, Yahweh overturned this worldview. Pharaoh may have been treated as a demigod, but Moses was elevated to a higher status by direct commission from the God of gods. Pharaoh claimed partial divinity by birth and ritual, but Moses was given full elohim authority through Yahweh’s word. The shepherd from Midian stood above the god-king of Egypt, not because of his own nature but because he carried the authority of the Most High. The conflict that follows in the plagues is not merely political but a spiritual contest that exposes Pharaoh’s claims as fraudulent and reveals Yahweh’s supremacy.

Theological Significance

These passages reveal the nature of delegated authority. Yahweh does not need Moses, but He chooses to work through him, making His servant the visible manifestation of His will before both His people and His enemies. This is not about deification but about representation. It also points toward the divine council pattern, where Yahweh’s authority is mediated through appointed beings who act on His behalf. The difference with Moses is that he is human, given temporary status as elohim for a specific mission.

In the larger biblical story, this anticipates a greater contrast. Moses functions as elohim to Aaron and Pharaoh, but he only mediates the words given to him. Christ, by contrast, is not merely in the role of elohim but is Himself Yahweh incarnate. He does not speak as a mouthpiece but as the divine Word made flesh. The authority delegated to Moses finds its ultimate fulfillment in the authority inherent in Christ.

Conclusion

When Yahweh declared that Moses would be elohim to Aaron and to Pharaoh, He was revealing how His authority operates in history. He invests His representatives with His own status so that His purposes are unmistakable. This was a challenge to Egyptian pretensions of divinity, an encouragement to Israel, and a glimpse of the way God works through chosen servants. Above all, it foreshadowed the one who would not only represent Yahweh but would be Yahweh Himself, dwelling among His people.

Discussion Questions

- What does the use of the word elohim for Moses tell us about the flexibility of this Hebrew term?

- How does the chain of communication between Yahweh, Moses, and Aaron illustrate the nature of prophetic authority?

- In what ways was Pharaoh’s role as a demigod similar to the Nephilim, and how does that sharpen the meaning of Moses as elohim?

- How does Moses’ delegated authority point forward to the greater authority of Christ?

- What does this passage teach us about God’s choice to work through human representatives rather than bypass them?

Want to Know More?

- Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible

Heiser explores the meaning of elohim, the divine council, and spiritual authority throughout the Old Testament. His discussion directly supports the idea of Moses being appointed to act with divine status in Exodus 4 and 7. - John H. Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament

This work provides essential background on the worldview of the ancient Near East, including how kings were viewed as divine and how the biblical authors engaged with and subverted those ideas. - Terence E. Fretheim, Exodus (Interpretation Commentary Series)

Fretheim offers a theological reading of Exodus that emphasizes Moses’ unique prophetic role and his function as a representative of Yahweh before both Israel and Pharaoh. - Brevard S. Childs, The Book of Exodus: A Critical, Theological Commentary

A respected scholarly commentary that carefully analyzes the structure and meaning of the text, including Yahweh’s commissioning of Moses and the concept of divine agency. - Nahum M. Sarna, Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel

Sarna blends scholarship with accessible language to explain the cultural and religious dynamics at play in the Exodus account, particularly the confrontation between Yahweh and Pharaoh’s claimed divinity.