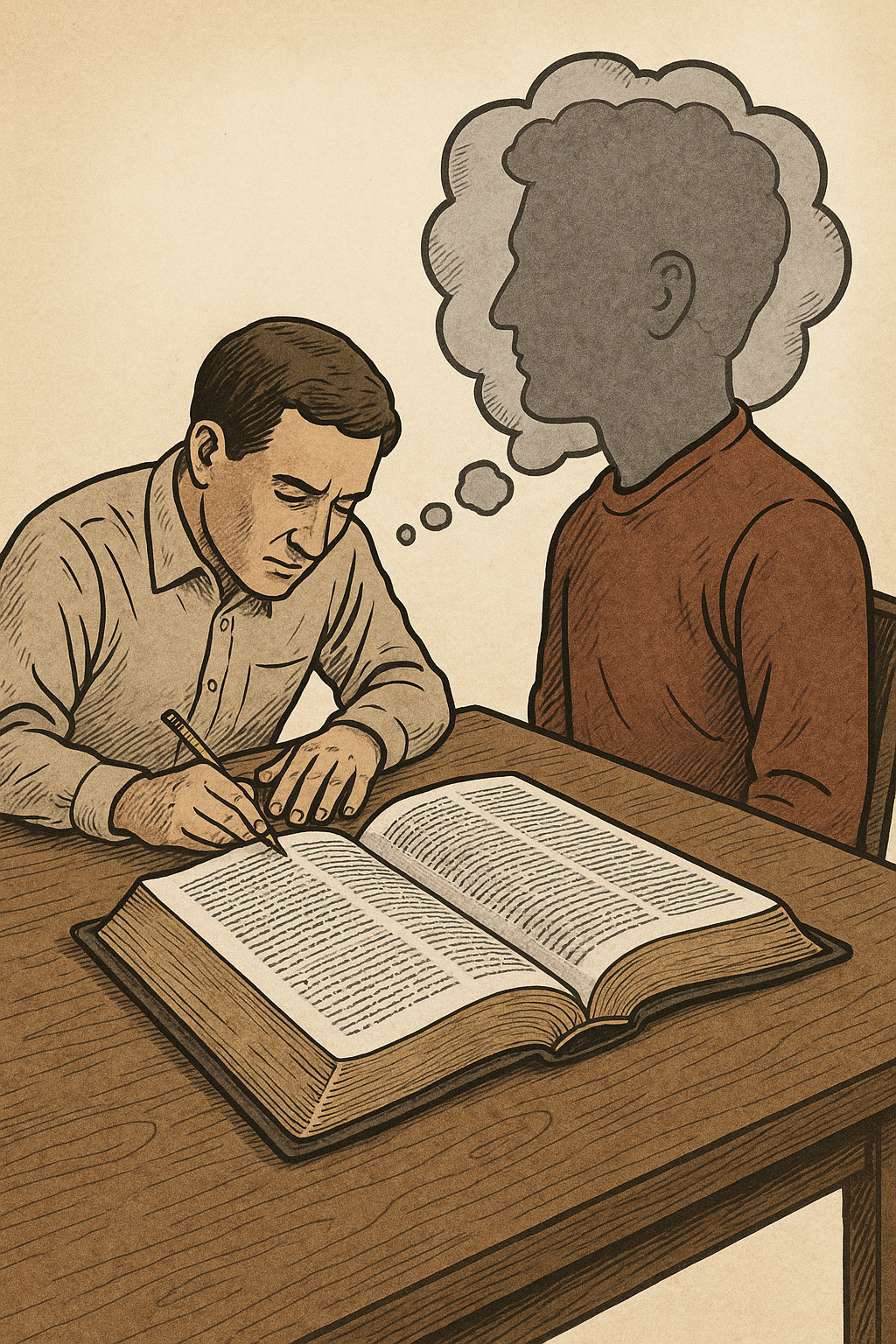

When we read the Bible, we never approach it as a blank slate. We bring assumptions, cultural filters, personal experiences, and expectations. Scripture, however, demands that we lay those things down. The way we approach the Bible determines whether we are hearing God’s voice or simply amplifying our own. This is where the distinction between exegesis and eisegesis becomes critical.

Exegesis is the process of drawing meaning out of a biblical passage based on its context, grammar, historical background, and literary structure. The term comes from a Greek word meaning “to lead out.” It asks what the author intended to communicate to the original audience and what God is saying through that text.

Eisegesis, on the other hand, means “to lead into.” It involves importing one’s own ideas or assumptions into the text, whether consciously or not. While it may sound harmless, eisegesis can distort theology, promote error, and mislead sincere readers.

Laodicea and the Lukewarm Church

Revelation 3:16 says, “So, because you are lukewarm, neither hot nor cold, I am about to spit you out of my mouth.” A common interpretation suggests that Jesus prefers people to be either fully committed or openly rebellious rather than half-hearted. But this understanding contradicts the consistent call in Scripture for repentance and faith.

Laodicea’s geography explains the metaphor. The city sat between Colossae, known for cold, refreshing water, and Hierapolis, famous for its hot springs. By the time water reached Laodicea through aqueducts, it was lukewarm, mineral-heavy, and unpleasant. Jesus is not comparing spiritual passion and apathy. He is saying the church had become spiritually useless, offering neither refreshment nor healing. Exegesis brings this context to light. Eisegesis misreads the metaphor entirely and turns the passage into a strange statement about God’s preferences.

Two or Three Gathered

Matthew 18:20 is frequently quoted to affirm the power of small group prayer: “For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.” While it sounds encouraging, the verse does not refer to prayer meetings or informal worship. In context, it concludes a section on church discipline. Jesus is assuring His followers that when they faithfully carry out difficult acts of correction or accountability within the church, His authority is present in their decisions.

Used out of context, the verse suggests that Jesus is only present when multiple believers are gathered, as if He abandons solitary prayer. Exegesis clarifies that His presence is not limited by numbers. Eisegesis strips the verse from its legal and communal context and weakens other promises, like His assurance in Matthew 28 that He is with us always.

Where There Is No Vision

Proverbs 29:18 in the King James Version says, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” This verse is often quoted at leadership conferences or planning meetings to emphasize the need for goals and mission statements. However, the Hebrew word translated “vision” refers to divine revelation, not personal ambition.

The full verse, which is often overlooked, says, “but blessed is he who keeps the law.” This makes the meaning clear. When people reject or are deprived of God’s instruction, moral chaos follows. Exegesis connects the verse to biblical authority and obedience. Eisegesis treats it as a motivational slogan and detaches it from the seriousness of spiritual rebellion.

Putting Away Childish Things

In 1 Corinthians 13:11, Paul writes, “When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me.” This is often used in messages about growing up emotionally or assuming adult responsibilities. But Paul is not giving a general commentary on personal development.

Instead, he is describing the difference between our present, limited spiritual understanding and the complete knowledge we will have when we are in the presence of God. This verse fits into Paul’s broader message about love enduring beyond spiritual gifts and current limitations. Exegesis places the passage within this eschatological framework. Eisegesis hijacks it for surface-level advice about maturing.

All Things for Good

Romans 8:28 is one of the most frequently cited verses in times of difficulty: “And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose.” The comfort is real, but the meaning is often misunderstood. People assume this verse guarantees that every trial will end in material blessing or emotional closure.

Yet in the surrounding verses, Paul speaks about groaning, suffering, weakness, and the hope of redemption. The “good” that God works toward is not comfort or success but our conformity to the image of Christ and participation in His eternal glory. Exegesis keeps the focus on God’s eternal purpose. Eisegesis turns the verse into a false promise of temporary ease, which can lead to disappointment and doubt when things do not improve quickly.

Conclusion

Reading the Bible faithfully requires discipline, humility, and a willingness to be corrected. Exegesis draws us into the world of the text. It requires that we listen before we speak, observe before we assume, and seek God’s meaning rather than our own. Eisegesis reverses that process. It turns the Bible into a mirror for our own ideas, even when those ideas conflict with the truth.

These five examples show how easily we can twist Scripture when we ignore its context. Misinterpretation may start small, but over time it weakens theology, confuses believers, and gives false confidence in promises God never made. When we allow the Bible to speak clearly and consistently, even hard truths become life-giving. That is the task of every student, teacher, and follower of Christ.

If we are serious about discipleship, we must be serious about interpretation. Scripture is not a tool for affirming our desires. It is the voice of the living God, calling us into truth. And the only way to hear that voice rightly is to let the text lead—and to leave our own agendas behind.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think eisegesis is so common, especially in modern devotional or motivational uses of Scripture?

- How can we guard against reading our own ideas into the text?

- What tools or habits can help us become better at exegesis?

- How might improper interpretation of verses affect someone’s faith or expectations?

- Do you think it’s ever okay to use a verse devotionally if it’s not the original meaning? Why or why not?

Want to Know More?

- Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth. A classic guide that helps readers interpret Scripture accurately and responsibly.

- Michael J. Gorman, Elements of Biblical Exegesis. Offers a step-by-step method for drawing meaning from Scripture in context.

- D. A. Carson, Exegetical Fallacies. Helps readers avoid common errors when interpreting the Bible.

- John Walton, The Lost World of Scripture. Explores the cultural and linguistic context of ancient Israel and the biblical text.

- N. T. Wright, Scripture and the Authority of God. Discusses how the Bible functions as God’s authoritative word in the Church.