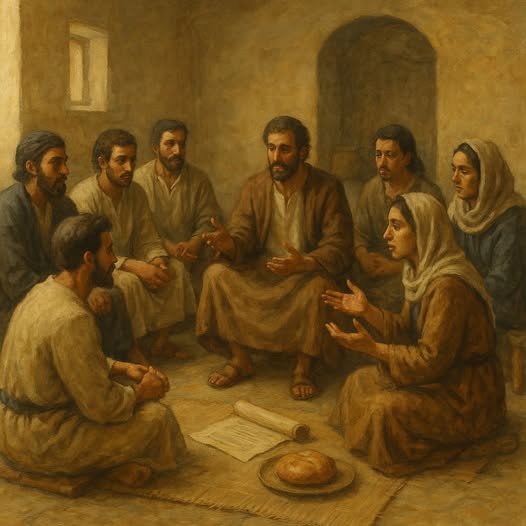

The early Christian church, though born in the simplicity of house gatherings and grassroots evangelism, revealed a surprisingly coherent organizational structure rooted in mutual service and spiritual authority. Far from being a chaotic or purely spontaneous movement, the apostolic church exhibited an intentional form of governance. This structure was centered around two primary leadership roles: elders and deacons. Yet it remained grounded in communal accountability and spiritual gifting. Questions about the involvement of women in these roles and the financial integrity of the early church add further texture to our understanding of how the first believers lived out their faith in community.

Elders and Deacons: The Two-Tiered Framework

The New Testament outlines a clear two-tiered model of leadership, emphasizing spiritual oversight through elders and practical service through deacons.

Elders (Greek: presbyteroi, episkopoi) were charged with shepherding the flock, safeguarding sound doctrine, and providing spiritual guidance. The qualifications for elders in 1 Timothy 3:1–7 and Titus 1:5–9 reflect high standards of moral integrity, family leadership, and teaching ability. These leaders were not simply administrators but spiritual shepherds entrusted with the well-being of the community’s soul.

Deacons (Greek: diakonoi, meaning servants or ministers) were responsible for practical care, ranging from distributing food and aid to maintaining unity within the congregation. The account in Acts 6, where seven men are appointed to oversee food distribution so the apostles could focus on prayer and the Word, is often cited as the origin of this role. Paul’s instructions in 1 Timothy 3:8–13 emphasize similar moral standards for deacons, while also recognizing their influential role within the body.

This structure, while organized, was never intended to resemble the rigid hierarchies of later centuries. It was relational, cooperative, and focused on service rather than control.

Oversight: Elders as Shepherds, Not Monarchs

Oversight in the early church was typically handled by elders, who are also referred to as overseers (episkopoi) in texts like Titus 1:7 and Acts 20:28. These terms were often interchangeable, reflecting function rather than rank. Their task was multifaceted: teaching sound doctrine, correcting error, offering pastoral care, and when necessary, disciplining members (1 Timothy 5:19–20).

The Greco-Roman world used the term episkopos for officials who inspected civic matters or managed estates on behalf of another. In the Christian context, it carried the weight of stewardship under Christ’s authority. But crucially, the New Testament never presents these leaders as solitary rulers. The Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15) demonstrates a model of collective decision-making involving apostles and elders alike. This collegial approach suggests a framework of accountability and mutual discernment, not clerical dominance.

Even in pastoral epistles, Paul addresses the plurality of elders in churches, such as those in Ephesus (Acts 20:17) and Crete (Titus 1:5). Authority was exercised in relationship and in service, not in personal ambition or power.

The Role of Women in Early Church Leadership

The question of women in leadership within the early church is complex but not without biblical grounding. The most explicit reference is found in Romans 16:1, where Paul commends Phoebe as a diakonos of the church at Cenchreae. The term is the same used for male deacons, suggesting a recognized office rather than a generic description of service. Paul also refers to her as a prostatis, or patron, implying she held both influence and authority.

The reference in 1 Timothy 3:11 has long been debated. Some translations interpret the verse as referring to the wives of deacons, but the Greek allows for an alternative reading: “Likewise, the women must be dignified…” This parallel construction hints that Paul may be addressing female deacons directly.

The case for female elders is more ambiguous. Some suggest that the “elect lady” in 2 John may have been a female house church leader. While speculative, it is consistent with early church practice where house churches were often led by those who hosted them. In the third-century Didascalia Apostolorum, we find references to female deacons, showing that by this point, women were engaged in recognized ministry roles, especially in ministering to other women.

While Scripture limits certain roles (such as in 1 Timothy 2:12–15), it clearly affirms women as fellow workers, prophets (Acts 21:9), and key supporters of the gospel mission.

Financial Stewardship and Communal Support

The early Christian approach to finances was rooted in generosity, voluntary sharing, and trust. Acts 2:44–45 describes believers holding “all things in common,” selling property and possessions to meet needs within the community. Acts 5:1–11 shows that this was voluntary, not enforced, as Peter emphasizes that Ananias was under no obligation to give or misrepresent the amount.

Paul also organized financial collections for the Jerusalem church, calling for generous, cheerful giving (2 Corinthians 8–9). He emphasized transparency and accountability by sending trusted individuals to oversee the funds (2 Corinthians 8:16–24). The goal was not a redistributionist system, but mutual care between congregations and a tangible expression of unity across ethnic and regional lines.

Conclusion

The structure of the early Christian church reveals a community shaped by service, not status. It was led by collective discernment, not centralized control. Elders and deacons formed the backbone of spiritual and practical leadership, while women played essential, though sometimes overlooked, roles in ministry. Financial giving was voluntary, generous, and oriented toward meeting needs, not accumulating wealth or enforcing equality by force.

This vision of the church, a body with many members working together in love and purpose, offers a vital corrective to both authoritarian and overly egalitarian models of church governance today. It also calls modern believers to uphold integrity, mutual responsibility, and Christlike leadership in every aspect of church life.

Discussion Questions

- How does the early church’s two-tiered structure challenge or confirm current models of church leadership?

- What can we learn from the plurality of elders in the New Testament about accountability and shared authority?

- How should the biblical examples of Phoebe and others shape our understanding of women’s roles in ministry?

- In what ways does the voluntary financial system of the early church contrast with modern ideologies like Communism?

- How does collective decision-making in Acts 15 inform our approach to resolving doctrinal disputes today?

Want to Know More?

- Jeramie Rinne, Church Elders: How to Shepherd God’s People Like Jesus

A practical, biblically grounded exploration of the elder’s role that emphasizes servant leadership and spiritual responsibility. - Robert Banks, Paul’s Idea of Community: The Early House Churches in Their Cultural Setting

This classic work delves into the relational and communal structure of Pauline churches and their leadership patterns. - Wayne A. Meeks, The First Urban Christians: The Social World of the Apostle Paul

Offers sociological insights into the earliest Christian communities and how leadership and finances operated in their urban settings. - Carmen Imes, Being God’s Image: Why Creation Still Matters

While broader in scope, this work sheds light on how early Christians understood calling, vocation, and community responsibility within the body of Christ. - Everett Ferguson, Church History: Volume One, From Christ to the Pre-Reformation

Includes detailed descriptions of early church governance, the role of women, and financial practices in the first three centuries.