In modern usage, the word myth often implies fantasy or falsehood. However, in the context of the Ancient Near East (ANE), myths served as cultural memory, foundational stories that explained a people’s origin, destiny, and relationship to the divine. When we speak of “myth” in this article, we are not equating the biblical record with fiction, but highlighting how the inspired authors of Scripture often engaged with and subverted the prevailing myths of surrounding nations. The result is not imitation, but correction, a divine rebuttal to corrupted traditions that once held fragments of truth before being twisted by rebellious celestial beings.

The Ancient Near Eastern Hero: Demigods and Divine Kings

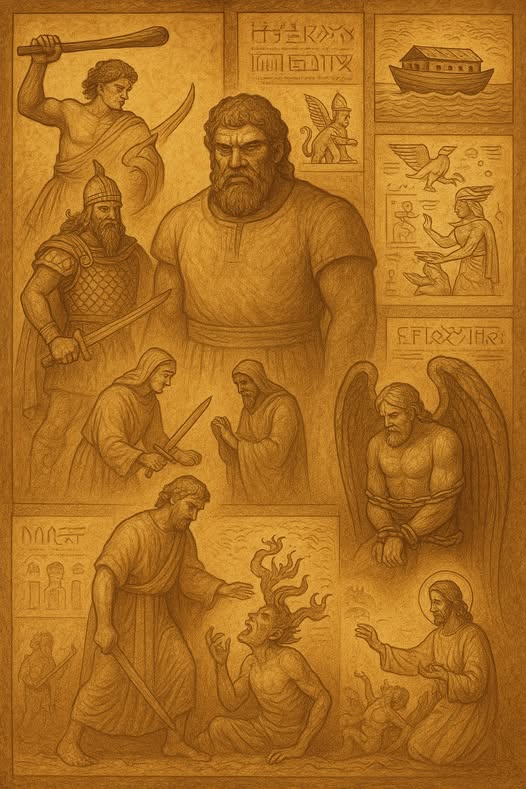

Many ancient civilizations preserved stories of exceptional beings born of both human and divine parentage. In Greek mythology, figures such as Hercules, Perseus, and Achilles embodied the heroic ideal. They possessed superhuman strength or destiny, often served as defenders of their people, and were treated as semi-divine. These stories provided theological justification for leadership, conquest, and cultural superiority.

This idea was not exclusive to the Greek world. In Sumer, Gilgamesh was described as two-thirds divine, a king whose journey for immortality revealed both grandeur and futility. In Egypt, pharaohs were considered sons of gods like Ra or Osiris, divine intermediaries who ruled not merely by bloodline but by cosmic right. The Hittites and Canaanites also had stories of heroic or god-descended kings who shaped their civilizations.

Outside the ANE and Mediterranean basin, the theme of divine-human offspring also appears. In Hindu tradition, heroes like Bhishma or Karna in the Mahabharata are born of human mothers and divine fathers, Vasu and Surya, respectively. In the Norse sagas, heroes such as Sigurd or the lineage of Odin often blend the divine with the mortal, reflecting a cosmology of descent and legacy. In Chinese mythology, the Yellow Emperor was said to have divine origins, and in Japanese tradition, emperors claimed descent from Amaterasu, the sun goddess.

These narratives, though culturally distinct, all share a central thread: they elevate certain rulers or warriors above others by attributing to them divine parentage. They frame such individuals as predestined saviors, culture-bringers, or god-chosen kings whose semi-divine blood legitimized their power and prestige.

Against this widespread and deeply embedded pattern, the Bible presents a subversive and even confrontational narrative. Genesis 6 does not glorify divine-human hybrids. It condemns them. Rather than being celebrated as saviors or kings, the Nephilim are portrayed as violent oppressors. Their birth marks a cosmic rebellion, not a divine favor. Far from granting legitimacy, their existence calls down judgment.

This stark contrast sets the biblical worldview apart. Where other traditions honored the hybrid offspring of gods and men, the Bible exposes such unions as corruptions of divine order, leading not to flourishing, but to ruin.

Genesis 6: A Polemic of Judgment

Against this cultural backdrop, Genesis 6 delivers a jarring reversal. The “sons of God,” members of the heavenly host, intermingled with human women, producing the Nephilim. Rather than celebrating these hybrid offspring, the Bible condemns them. They were not noble heroes, but tyrannical giants who filled the earth with violence. Their birth was not a blessing to humanity, but a perversion of divine order.

This is no coincidence. The biblical narrative is directly confronting the belief that greatness stems from divine-human unions. It asserts instead that such unions were acts of rebellion, not divine will. The “heroes of old” remembered by pagan cultures were, in this light, the spawn of a cosmic crime.

The Corruption of Knowledge and the Echo of Prometheus

The rebellion of the Watchers, as expanded in 1 Enoch, included not just sexual transgression but the illicit dissemination of knowledge. Mankind was taught sorcery, astrology, weapon-making, and other forbidden arts. This aspect of the story likely lies behind the Greek tale of Prometheus, who defied the gods to bring fire, symbolic of divine knowledge, to humanity.

But where Prometheus is a tragic benefactor in Greek myth, the biblical narrative casts these acts as dangerous corruptions. The knowledge brought by the Watchers destabilized creation. Humanity, seduced by wisdom not meant for them, spiraled into sin and violence, necessitating divine intervention through the Flood.

The Flood: Resetting Creation

The judgment of the Flood is not simply about human sin. Genesis 6 attributes the crisis to the hybrid corruption introduced by the rebellious heavenly beings. In response, God preserves only Noah, a man who is “blameless in his generation,” which many scholars read as a reference to both moral and genealogical purity.

This divine reset purged the physical world of the Nephilim, but their spiritual legacy persisted.

The Return of the Giants: Canaan and the Davidic Wars

When Israel enters Canaan, they encounter remnants of the Nephilim, giant clans such as the Rephaim and Anakim. These beings were not simply tall humans but carried with them a memory of the earlier transgression. Moses, Joshua, and especially David are portrayed as God’s instruments in rooting out this evil legacy.

David’s battle with Goliath is not merely a story of an underdog triumphing over a warrior. It is a spiritual confrontation between God’s chosen king and the lingering offspring of rebellion. David’s mighty men, too, are noted for slaying giants, finishing the task that began in Genesis.

The Spirits of the Dead: Nephilim Become Demons

The Book of Enoch and various Second Temple texts go further. They claim that the disembodied spirits of the Nephilim became the demons that plague humanity in later ages. Because they were not created by God, these hybrid beings have no place in the heavenly realm. Upon death, they become restless, malevolent spirits that roam the earth.

This worldview provides the theological backdrop for the New Testament’s frequent exorcisms. Christ’s ministry is not only about forgiving sin and healing bodies. It is about confronting the ancient chaos that had plagued mankind since the days of Noah. Where David slew the giants, Christ casts out the demons, both actions declaring that the true King has come.

Contrasting Views: Greek Daimones vs. Biblical Demons

In ancient Greek thought, the term daimon did not originally carry a negative connotation. Daimones were regarded as intermediary spirits, sometimes associated with divine inspiration, guidance, or wisdom. Philosophers such as Plato described them as mediators between gods and humans, and Socrates spoke of his personal daimonion, a guiding voice or spirit that influenced his decisions.

This stands in stark contrast to the biblical view of demons as unclean spirits born from rebellion and corruption. In Scripture, demons are not helpful guides or protectors, but hostile forces that oppose God’s will. They deceive, torment, and possess, waging spiritual war against humanity.

This clash of worldviews had practical implications. As the early church spread into the Hellenistic world, it had to reframe common terminology. Words like daimonion could not be used without clarification, as their biblical use referred to entirely malevolent beings. The apostolic message redefined spiritual categories in light of divine revelation, exposing as deceptive what had once seemed benign or even virtuous.

A Sacred Rebuttal: The Bible as a Corrective Narrative

Rather than participating in the myth-making of ancient cultures, the Bible offers a divine critique. It acknowledges the memories preserved in those myths, of mighty beings, divine rebellion, catastrophic floods, and spiritual warfare, but reorients them around truth. Heroes like Gilgamesh and Hercules are echoes of a deeper story, warped by time and false gods.

The Holy Spirit did not inspire the biblical authors in a cultural vacuum. Instead, Scripture engages its context with purpose. The myths of the nations are not ignored, but confronted and redefined, revealing the power of Yahweh and the dangers of idolatry.

Conclusion

The biblical narrative does not emerge in isolation. It stands as a deliberate and theologically charged response to the myths, legends, and spiritual frameworks of the surrounding world. Where other cultures exalted demigods and divine kings, Scripture exposes them as the product of rebellion. Where pagan tales praised the transmission of forbidden knowledge, the Bible frames it as the catalyst for corruption and destruction.

Through its accounts of the Nephilim, the Watchers, and the flood, and later through the battles against giants and the ministry of Christ over demons, the Bible consistently reveals a God who confronts chaos, judges spiritual rebellion, and restores order. It reclaims the spiritual narrative, not by silencing the ancient voices, but by correcting them, bringing light where there was distortion, and truth where there was myth.

Discussion Questions

- How do the Nephilim in the Book of Genesis challenge or subvert the traditional concept of demigods or heroes found in other ancient mythologies?

- What parallels can be drawn between David’s campaign against the giants and Christ’s mission to defeat demonic forces?

- How might the story of the Nephilim and their transformation into demons be seen as a commentary on the misuse of power and the consequences of violating divine boundaries?

- How does the biblical view of demons differ from the Greek understanding of daimones? What are the implications of this difference?

- How does understanding the surrounding mythologies help modern readers better appreciate the theological precision of the Bible?

Want to Know More?

- The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible by Michael S. Heiser

Explores the biblical context of the divine council, the Nephilim, and how ancient worldviews shape Scripture’s supernatural claims. - Demons: What the Bible Really Says About the Powers of Darkness by Michael S. Heiser

Traces the biblical origin of demons from Genesis through Revelation, showing how they stem from the rebellion of the Watchers. - Reversing Hermon: Enoch, the Watchers, and the Forgotten Mission of Jesus Christ by Dr. Michael Heiser.

Argues that Christ’s mission directly confronts the fallout of the Genesis 6 rebellion and the influence of the Watchers. - Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature by Benjamin R. Foster

A primary source collection of Sumerian and Akkadian myths that helps illuminate the background of biblical polemics. - Myth and Reality by Mircea Eliade

Examines how myths function as sacred history, helping readers understand how the Bible interacts with ancient narratives.