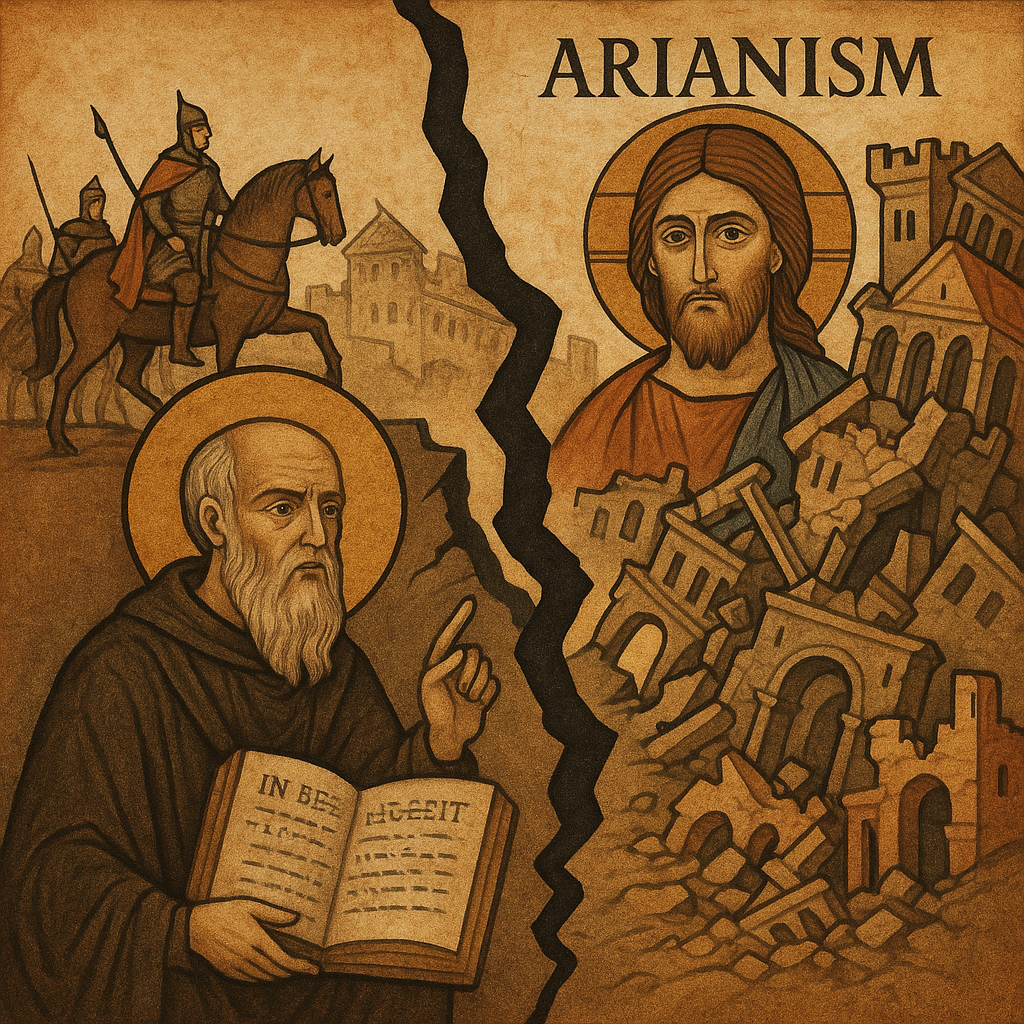

Arianism was more than a theological dispute; it became a force that rattled the foundations of the Roman Empire. Originating with the Alexandrian priest Arius (AD 250–336), the doctrine asserted that the Son, Jesus Christ, was a created being and therefore not co-eternal with the Father. This challenged the traditional Christian understanding of Jesus’ divinity and ignited a controversy that tore through the Church and empire alike.

By the time of Constantine in the early 4th century, Christianity had been legalized and heavily promoted, though not yet made the official religion of Rome. Constantine’s patronage brought Christianity into the center of imperial life, and his calling of the Council of Nicaea in 325 demonstrated just how closely church and empire were becoming linked. Yet the settlement of Nicaea did not resolve the issue. The Arian controversy lingered, splitting bishops, congregations, and emperors.

What began as a debate over the Trinity soon spiraled into a crisis that divided the empire at its core. As Arianism spread, particularly among the Germanic tribes who would later overrun the Western Empire, the theological rift turned into a political fault line. In this way, a doctrinal battle over Christ’s divinity became bound up with the very fate of Rome itself.

Why Arianism Was Declared a Heresy

The Church declared Arianism a heresy at the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325. The fundamental issue revolved around the nature and divinity of Jesus Christ. While Arius believed Jesus was a creation—albeit the highest of all creations—the Church upheld that Jesus was uncreated, co-eternal, and co-equal with the Father.

Scripture played a decisive role in the dispute. John 1:1 states, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” This verse affirms the divinity of Jesus, describing Him as the Word who both existed at the beginning and was God Himself.

Colossians 1:16 likewise insists on Christ’s active role in creation: “For by him [Jesus] all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him.” Such passages undermine the Arian claim that Jesus Himself was a creation.

Arianism and the Fall of Rome

Arianism’s role in the fall of Rome was indirect but profound. The empire’s collapse stemmed from many interwoven factors—economic strain, military overreach, and external invasions—but theological division turned these pressures into crises.

After the Council of Nicaea, Arianism did not disappear. Instead, it spread widely, especially among the Germanic tribes that increasingly interacted with the empire. Missionaries like Ulfilas translated the Scriptures into Gothic and taught them Arian theology, ensuring that groups such as the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, and Burgundians entered Roman territory not as pagans but as adherents of a rival Christianity.

This created a serious wedge. To Nicene Romans, the newcomers were heretics who could never be fully trusted. To the tribes themselves, the Roman Church appeared hostile, dismissive, and foreign. Religious division compounded cultural difference, making assimilation nearly impossible. Instead of binding diverse peoples under one creed, Christianity became a fault line that hardened tribal identity.

The situation worsened when emperors and generals exploited these divisions, using Arian allies against Nicene rivals, or favoring one faction of bishops over another. In doing so, the empire allowed theology to become a weapon of politics, and politics to become hostage to theological disputes.

When the invasions intensified in the 4th and 5th centuries, Rome was not simply facing external enemies—it was confronting Christian tribes who had already rejected the empire’s version of orthodoxy. The split between Arian and Nicene Christianity meant that these groups were not integrated partners but competitors for authority and legitimacy. This failure of unity, rooted in the Arian controversy, magnified Rome’s vulnerability and hastened the fall of the Western Empire.

The Death of Arius

The death of Arius became infamous, both for its suddenness and its symbolism. According to Socrates of Constantinople in his Ecclesiastical History, Arius was about to be formally readmitted into communion in Constantinople under imperial pressure. His apparent triumph was short-lived.

As he processed toward the great church of Hagia Sophia, Arius was suddenly seized by violent stomach pains. Seeking privacy, he entered a public restroom. There, he suffered a catastrophic internal hemorrhage. Witnesses later reported a gruesome scene: Arius died in agony, humiliated, and alone.

To his opponents, this was no mere coincidence but divine judgment. His dramatic end was used as a cautionary tale, reinforcing the conviction that God Himself had condemned Arianism.

Aftermath and Legacy

Even after Arius’s death, his teaching endured for centuries, particularly among the Germanic tribes that shaped post-Roman Europe. The Ostrogoths in Italy, the Visigoths in Spain, and the Vandals in North Africa all adhered to Arian Christianity. For a time, it seemed that Arianism would define the Christian identity of the post-Roman West.

The decisive turning point came with the conversion of the Franks. In the late 5th century, King Clovis I accepted Nicene Christianity rather than Arianism, aligning his kingdom with the Roman Church. This decision was both religious and political: it gave the Franks legitimacy in the eyes of the Papacy and set them apart from neighboring Arian kingdoms. As the Franks expanded their power, their Nicene allegiance allowed them to present themselves as defenders of orthodoxy, winning the support of the Catholic clergy and population under Arian rule.

Over time, one by one, the Germanic kingdoms abandoned Arianism. The Visigoths converted to Nicene Christianity at the end of the 6th century, followed by others. By the 7th century, Arianism had virtually disappeared from Europe.

Its impact, however, was lasting. The Nicene Creed, first formulated to counter Arianism, remains a cornerstone of Christian confession to this day. The controversy also pushed the Church to refine its understanding of Christology and the Trinity, culminating in further ecumenical councils, including the Council of Constantinople (381) and the Council of Chalcedon (451). These established doctrines affirmed Christ as both fully divine and fully human, truly God and truly man.

Conclusion

Arianism was more than a passing theological error. It ignited one of the fiercest doctrinal battles in Church history and widened fractures that weakened the Roman Empire from within. By fueling division among Christians and becoming the religion of the very tribes who dismantled Rome’s Western power, Arianism became inseparable from the story of imperial decline.

Though ultimately defeated and declared heresy, Arianism forced the Church to sharpen its doctrine of Christ’s divinity and unity with the Father. It left behind the Nicene Creed as both shield and testimony—an enduring monument to a struggle where theology and empire collided, and Rome itself fell amid the turmoil.

Discussion Questions

- Why was the hierarchical view of the Trinity proposed by Arius so controversial, and how did it challenge the existing understanding of Jesus’ divinity within the early Church?

- How did Arianism contribute to the political and religious fragmentation of the Roman Empire?

- What role did Scripture play in the refutation of Arianism, and which passages most directly countered Arius’s teaching?

- The death of Arius was portrayed as divine judgment. What does this reveal about how theological disputes were framed and understood in the early Church?

- In what ways did Arianism’s persistence among the Germanic tribes shape the post-Roman world before its eventual decline?

Want to Know More?

- Rowan Williams, Arius: Heresy and Tradition – A foundational study of Arius, his theology, and the long-term effects of the controversy.

- Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization – A detailed account of Rome’s collapse, showing how internal divisions, including religious strife, weakened the empire.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History – A 5th-century primary source describing Arius’s death and the debates surrounding his followers.

- R.P.C. Hanson, The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy 318–381 – A comprehensive analysis of the theological arguments and political struggles surrounding Arianism.

- J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines – A classic introduction to early doctrinal development, including the Church’s response to Arianism.