The title “King of the Jews” appears only a few times in the Gospels, but every mention is explosive. It is not simply a political label. It is a theological challenge, a prophetic fulfillment, and a declaration of authority that cuts across heaven and earth. Herod the Great bore that title, not by inheritance, not by divine call, but by imperial decree. Jesus bore the same title, not by the will of man, but by the will of God.

The clash between Herod and Christ was not a passing episode. It was the unveiling of two competing kingdoms: one propped up by Rome, rooted in fear, and doomed to fall; the other eternal, meek in appearance, but unstoppable in power.

The Senate’s Declaration: Rome Appoints a King

Herod’s path to the throne was paved in Roman marble, not biblical prophecy. The Hasmonean dynasty had fractured into civil war. In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey was invited into Judea to resolve a dynastic struggle between Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. Pompey chose Hyrcanus and made Judea a Roman client state, setting the stage for imperial interference in Israel’s kingship.

Behind Hyrcanus stood Antipater the Idumean, Herod’s father, who became a powerful advisor and later procurator under Julius Caesar. Antipater appointed Herod over Galilee, where he quickly earned a reputation for efficient and ruthless governance. Rome took notice.

When a Parthian invasion in 40 BCE temporarily removed Roman control and installed Antigonus, a Hasmonean, Herod fled to Rome. There, with the backing of Mark Antony and Octavian, he petitioned the Roman Senate to recognize him as the new king of Judea. The Senate obliged. In a formal ceremony inside the Capitol, they declared Herod “King of the Jews.”

Armed with Roman legions, Herod returned to Judea and fought for three years before capturing Jerusalem in 37 BCE. He executed Antigonus, ending the Hasmonean line, and took the throne by force. His rule was never accepted by all. He knew his claim was fragile. That is why he married into the Hasmonean family, built the Temple, and eliminated rivals. His kingship had nothing to do with covenant, prophecy, or divine appointment. It was imposed by the will of the empire.

So when the Magi arrived and asked, “Where is he who has been born King of the Jews?” Herod heard far more than a curious question. He heard a direct challenge to the foundation of his power.

Herod the Great: Rome’s King

Herod was an Edomite, a descendant of Esau, whose ancestors had been forcibly converted to Judaism a generation earlier. He was not from the line of David, not born in Judah, and not chosen by the God of Israel. He ruled not by lineage or prophetic fulfillment but by Roman sanction.

To strengthen his claim, Herod married Mariamne, a Hasmonean princess from the former Jewish ruling dynasty. But even that was not enough to calm his insecurity. He later executed her, along with her brother and eventually her children, out of fear they might challenge his authority.

Herod’s entire kingship was an act of overcompensation. He built palaces, fortresses, cities, and most notably, he began an unprecedented expansion of the Jerusalem Temple. Though hailed as a religious act, the construction served political purposes. It was Herod’s attempt to portray himself as a faithful Jew and patron of Israel’s worship. It was also a calculated move to win the favor of the people and the priesthood.

Herod ruled as a vassal of Rome. His title was Roman. His throne stood at Caesar’s pleasure. His power was a symbol of empire, not covenant.

The Birth of the True King

The Gospels are clear: Jesus was born in Bethlehem, the city of David, in fulfillment of prophecy. He was not made king by Rome. He was born King. His identity did not require ceremony or endorsement. It had been foretold by Isaiah, Micah, and the entire prophetic tradition of Israel.

Herod was troubled. He consulted the chief priests and scribes, learned that the Messiah would come from Bethlehem, and reacted not with awe, but with fear. When the Magi failed to report back, he ordered the execution of every male child in Bethlehem under two years old.

This was not random violence. It was calculated and deliberate. Herod ruled a throne built on suspicion and blood. He saw in the child not a spiritual leader, but a rival king. And he responded the way counterfeit rulers always do when confronted with the real heir—he tried to destroy him.

King of the Jews: Two Crowns, One Conflict

Herod ruled from Jerusalem, wearing a crown placed on his head by Caesar. Jesus was born in obscurity, laid in a manger, and wore no crown. Herod’s reign was secured by legions. Jesus’s kingdom would grow without violence, carried by the poor in spirit and the meek who would inherit the earth.

Herod built the Temple to gain favor with men. Jesus would later declare that His body was the true Temple. Herod’s title came from the Senate. Jesus’s title came from heaven. One ruled by decree. The other by fulfillment.

Isaiah had declared that a child would be born and the government would rest on His shoulders. Micah had foretold that out of Bethlehem would come a ruler. Herod knew these scriptures. So did the priests. Yet it was pagan Magi who recognized the child. Herod sought to eliminate Him. The Magi sought to worship.

The Fall of Herod’s House

Herod died in Jericho in 4 BCE, consumed by disease, paranoia, and failure. His kingdom was divided among his sons and quickly diminished. One of those sons, Herod Antipas, would later mock Jesus. Another descendant, Herod Agrippa, would persecute the early Church. None of them understood what was unfolding before them. They clung to a fading throne, fighting a kingdom they could not see.

Jesus, by contrast, rose from Galilee, ministered among the poor and despised, and moved toward Jerusalem not to seize power, but to lay down His life. He was rejected, condemned, and crucified. Yet His death was not a defeat. It was enthronement.

From Galilee to Jerusalem: The Counterfeit Path

It is no accident that Herod’s career began in Galilee. That northern region was politically marginal, distant from the Temple, and easier to control. Herod proved himself there to Roman generals, then moved inward, eventually taking Jerusalem by force. His path was one of ambition and conquest. He went from the edges to the center, not to serve God’s covenant, but to dominate it.

This mirrors, yet opposes, the path of Jesus. Christ was born in Bethlehem, in the heart of Judah, the royal city of David. But He was raised in Galilee, the land long associated with spiritual darkness and foreign oppression. That is where He proclaimed the kingdom, healed the outcast, taught the humble, and called disciples. When the time came, He did not march into Jerusalem with soldiers, but entered in full view of the people, riding on a donkey.

This was not a gesture of humility alone. It was a deliberate royal claim. In the Ancient Near East, donkeys were not the mounts of beggars, but of kings in times of peace. Solomon had ridden his father David’s mule to be publicly declared king. The prophet Zechariah had foretold that Zion’s king would come “righteous and having salvation, humble and mounted on a donkey.” Jesus chose that mount not because He lacked a horse, but because He came not as a conqueror, but as the promised Son of David.

The crowd recognized the symbolism. They waved palm branches and cried out, “Hosanna to the Son of David!” They were not welcoming a mere teacher. They were hailing a king.

Yet this king did not ascend a throne. He confronted the corruption in the Temple, taught with authority, and in the days that followed, was betrayed and arrested. He left Jerusalem carrying a Roman cross, not to seize power, but to fulfill His mission. Herod moved from Galilee to Jerusalem to take the throne. Jesus moved from Galilee to Jerusalem to be enthroned by way of suffering.

One came to enthrone himself through violence. The other came to save through sacrifice.

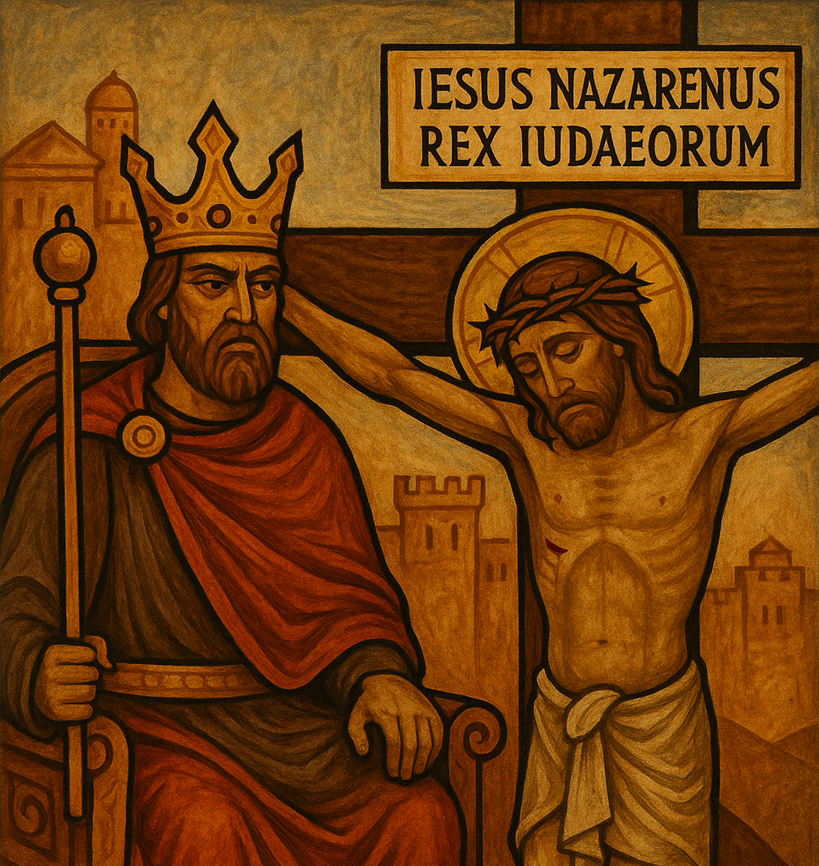

“King of the Jews” at the Cross

The final and most public use of the title “King of the Jews” occurs at the crucifixion. Pilate had the inscription placed above Jesus’s head: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” The priests protested, asking him to change it to say that Jesus only claimed the title. Pilate refused.

This sign, intended as mockery or political indictment, became an unintentional declaration of truth. Jesus was not simply the King of the Jews in a regional sense. He was the fulfillment of every covenant promise to Israel, and through Israel, to the world.

Crowned with thorns, robed in mockery, enthroned on a Roman cross, Jesus bore the title Herod once claimed. But unlike Herod, He would rise again. The throne was not seized. It was vindicated.

Conclusion

Herod was declared King of the Jews by Rome’s Senate. Jesus was declared King of the Jews by heaven and prophecy. Herod ruled by fear, constructed temples, and executed his rivals. Jesus ruled by grace, became the Temple, and laid down His life for His enemies. Herod is gone. His throne is dust. Jesus reigns forever.

One ruled by the will of men. The other rules by the will of God.

The true King still reigns.

Discussion Questions

- How does Herod’s appointment by the Roman Senate contrast with the prophetic promises concerning the true King of Israel?

- Why was the title “King of the Jews” such a threat to Herod, and how does that threat expose the difference between earthly and divine authority?

- In what ways does Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem on a donkey reflect both biblical prophecy and royal symbolism in the Ancient Near East?

- What does Herod’s path from Galilee to Jerusalem reveal about human ambition, and how does Jesus’s path from Galilee to Jerusalem reveal divine purpose?

- Why is it significant that the title “King of the Jews” reappears at the crucifixion, and how does this mockery become a declaration of truth in light of the resurrection?

Want to Know More?

- Peter Richardson, Herod: King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans

– A comprehensive and highly respected study of Herod’s political rise, Roman backing, architectural ambitions, and the religious-political tension surrounding his reign. Essential for understanding how Rome created Herod’s kingship. - Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (Revised by Vermes, Millar, and Black)

– A foundational academic work offering extensive historical background on the political, religious, and social structures of Judea in the time of Herod and Jesus. Includes coverage of Roman involvement and the Hasmonean collapse. - Craig A. Evans, Jesus and His World: The Archaeological Evidence

– Provides archaeological and historical insights into both Herodian construction projects and the historical reality of Jesus’s life and royal claims. Offers visual and contextual depth. - N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God

– A major theological work exploring Jesus’s mission, His fulfillment of messianic prophecy, and how His actions, including the entry into Jerusalem, directly challenged Rome and false kingship. - James H. Charlesworth (ed.), Jesus and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Controversy Resolved

– While broader in scope, this work sheds light on Second Temple messianic expectations and how figures like Jesus were understood in contrast to political rulers such as Herod.