In the Hebrew Bible, names are never just labels. They are theological markers, literary weapons, and prophetic declarations. To name someone or something was to define its identity and place in the cosmic order. For the biblical writers, especially the books of the prophets, renaming was often a tool of judgment. By altering names through wordplay or phonetic twists, they stripped enemies of dignity and exposed the futility of rebellion against Yahweh. These changes were not casual—they were intentional acts of ridicule aimed at showing that those who oppose the Most High are not to be feared, but to be laughed at, pitied, or remembered only in shame.

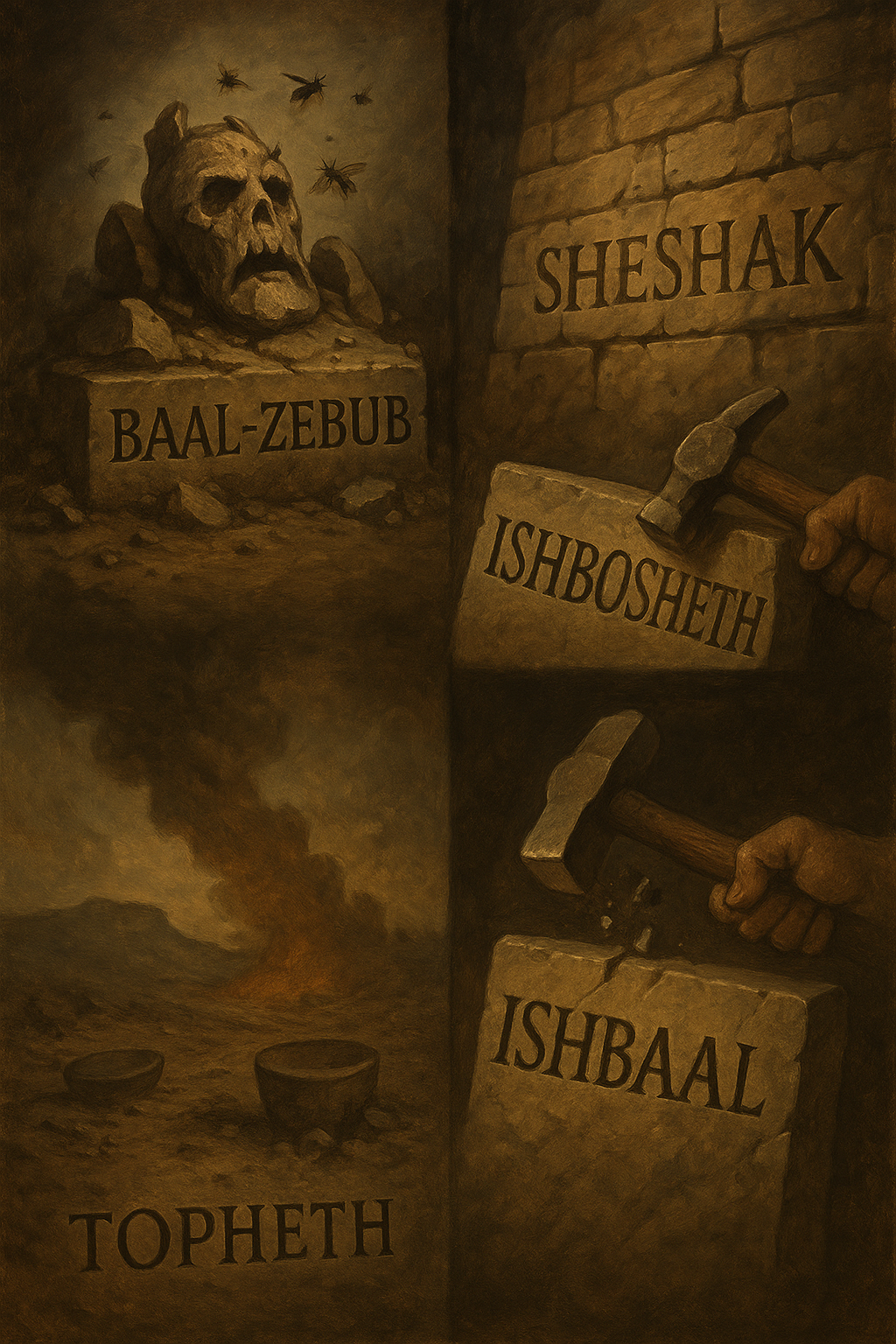

Baal-zebub: “Lord of the Flies”

In 2 Kings 1:2–3, King Ahaziah of Israel sends messengers to inquire of Baal-zebub, the god of Ekron. The original name was likely Baal-zebul—“Prince Baal.” But the text deliberately twists it into Baal-zebub—“Lord of the Flies.” This grotesque image transforms what was once a title of honor into a mockery of rot and decay. Flies are drawn to filth and death, and the implication is clear: Baal is not a prince, but a god of garbage and carrion. The name change is a theological slap in the face, not just to Baal, but to any Israelite king foolish enough to seek his counsel.

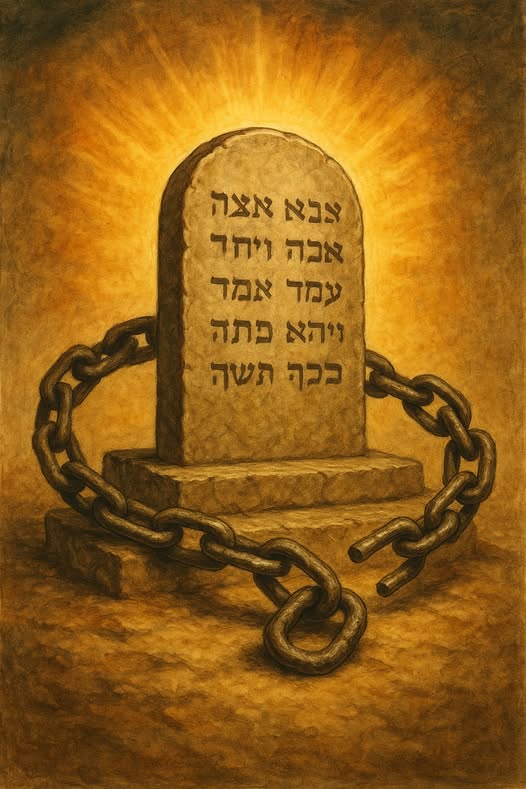

Sheshak: The Hidden Name of Babylon

In Jeremiah 25:26 and 51:41, the prophet refers to Babylon as Sheshak. This isn’t a scribal error—it’s a cipher known as atbash, where the Hebrew letters are replaced with their counterparts from a reversed alphabet. “Babel” becomes “Sheshak,” a cryptic but purposeful mockery. By encrypting the name, Jeremiah simultaneously veils the target for rhetorical effect and reveals that Babylon’s grandeur is an illusion. Even its name is being scrambled and broken down by the Word of God. Babylon, the empire of gold, is reduced to a riddle—and one destined for humiliation.

Merodach: Deflating the Babylonian God

In Jeremiah 50:2, Yahweh commands His people to declare, “Bel is put to shame, Merodach is filled with terror.” Merodach is the Hebrew form of Marduk, Babylon’s chief deity and the symbolic center of its imperial theology. By referring to him with a slightly mangled version of his name, the prophet subtly demotes him. It’s a stripping away of mystique. Rather than acknowledge him as a rival deity, the text presents him as a trembling failure—one whose time has come under Yahweh’s judgment.

Mephibosheth: Another Baal Erased

This same pattern appears with Mephibosheth, the son of Jonathan. In 1 Chronicles 8:34, he is called Meribbaal (“contender with Baal”), but in Samuel he is Mephibosheth—likely meaning something like “from the mouth of shame.” The shift follows the same formula as Ishbosheth’s: baal is replaced with bosheth. Even those in David’s own court who bore compromised names are retroactively renamed to reflect Yahweh’s honor and Baal’s humiliation.

Wordplay as Prophetic Polemic

The biblical practice of renaming enemies—and even former allies—is not petty mockery. It’s theological warfare. These transformed names proclaim that the gods of the nations are not rivals, but frauds. That kings who oppose Yahweh aren’t merely wrong, but ridiculous. That even Israel’s past flirtations with false gods deserve to be remembered with embarrassment, not nostalgia.

By weaponizing language, the biblical writers made sure that the enemies of Yahweh would not only be defeated but dishonored in memory. Their names live on, but only as ruins.

Conclusion: When Names Become Ruins

In the biblical worldview, words carry weight—and names carry legacy. By altering the names of Yahweh’s enemies, the biblical writers weren’t just being clever—they were making theological claims. These corrupted names became literary tombstones, monuments to pride, idolatry, and rebellion brought low. Whether mocking foreign gods like Baal and Marduk, renaming corrupted kings, or retroactively cleansing Israelite names of pagan associations, the message was consistent: Yahweh alone deserves honor, and those who oppose Him will not only fall—they will be remembered in shame.

Discussion Questions

- How does the alteration of “Baal-zebul” to “Baal-zebub” reflect the biblical writers’ view of false gods, and what imagery does it evoke?

- What is the purpose of using the Atbash cipher to rename Babylon as “Sheshak” in Jeremiah, and how does it reinforce the message of judgment?

- Why do names like “Ishbaal” and “Meribbaal” get changed to “Ishbosheth” and “Mephibosheth” in the biblical narrative? What message does this send to later readers?

- How does the modified spelling of “Marduk” as “Merodach” in Jeremiah 50:2 serve to diminish Babylon’s theological claims?

- What does the consistent pattern of renaming enemies and compromised figures suggest about the importance of names in Israel’s covenant identity?

Want to Know More?

Michael S. Heiser – The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible

Heiser discusses the theological messaging embedded in the biblical text, including the use of names, divine council motifs, and polemic against rival gods. His work helps contextualize how name changes function within a broader supernatural worldview.

Publisher: Lexham Press, 2015.

K.A. Kitchen – On the Reliability of the Old Testament

Kitchen provides linguistic and historical analysis of names, including the practice of polemical distortions against foreign gods and kings. He addresses how the biblical authors sometimes used altered forms of names to express disdain or theological judgment.

Publisher: Eerdmans, 2003.

Tremper Longman III – Jeremiah, Lamentations (New International Biblical Commentary)

In his commentary on Jeremiah, Longman explains the use of the Atbash cipher for “Sheshak” as a cryptic and mocking substitute for “Babylon,” offering historical and theological insight into the purpose behind this literary device.

Publisher: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008.

William F. Albright – Archaeology and the Religion of Israel (especially Chapter 6)

Albright discusses the cultural context of Baal worship and the Israelite response, including polemical name reversals like Baal-zebub. His work helps situate these name changes within the religious conflict between Yahwism and Canaanite religion.

Publisher: Johns Hopkins University Press, revised ed. 1968.

Robert Alter – The Art of Biblical Narrative

Alter’s foundational work on Hebrew literary techniques explores the intentional use of wordplay, irony, and naming as theological devices. While not focused exclusively on mockery, his analysis provides crucial insight into how name changes communicate narrative and moral judgments.

Publisher: Basic Books, revised ed. 2011.